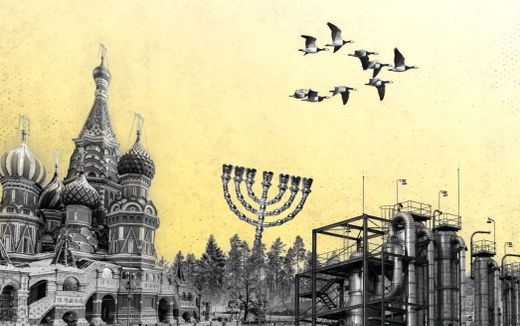

Essay: Believing amidst a nuclear threat

26-04-2022

Opinion

Bart-Jan Spruyt, RD

Photo EPA, Oleg Petrasyuk

Opinion

“In this country, every generation seems to be doomed to undergo for themselves as adults the terrible history that they learned as children at school,” wrote Pieter Waterdrinker a few years ago in the Dutch novel Lenins balsem (Embalming Lenin). He was describing Russia, but the same applies here in the Netherlands, and to my generation.

A tweet threatened to wreck my concentration. I’d booked off the whole of the early spring break: a full week to put the finishing touches to my book on the preacher of the early nineteenth-century Réveil (Protestant reawakening), J.W. Felix. But then Putin began his merciless invasion, and that meant for certain that I was going to be writing all week with the voices of upset journalists and confused commentators on the radio as background noise. It felt almost embarrassing to be sitting in a warm study, doing what I love most, while elsewhere in Europe people were fleeing bombs and other violence. And then came March 1, when that clip of an atomic bomb flashed past on Twitter—taking me right back to the Ossendrecht Barracks.

We used to have conscription in the Netherlands, you see: the state used to claim eighteen months of your life. On a Monday morning in summer 1984, I had to report to a desk at Bergen op Zoom railway station, where a truck came to take us off to Ossendrecht, an army base near the Belgian border. We were first taken to the quartermaster to have our standard personal kit issued (I still have it in the attic), and after that we were sent to a little hall to have a film played to us about nuclear attack. The idea was to impress upon us why we had National Service.

I recall that we did long marches in the woods around Breda, where—at a given signal—we had to dive under a tree and pull a hood up over our heads. Then we’d apparently be fine if “the Russians” dropped an atom bomb on us. This was how we were prepared for the anticipated mega battle on the North German Plain, where it was going to be our task to stop “the Russians” from advancing. On heathland near Ede, we went through a mock battle along the IJssel River, and three weeks later, a junior officer dropped in to notify us that we’d won the war.

Unprepared

The mid-Eighties was about the hottest that the Cold War ever got, but it took just five years from our “Battle for the IJssel” to the real-world fall of the Berlin Wall. Now, we really had won. We celebrated “the end of history”. Our liberal democracy had definitively beaten evil. So, what role remained for NATO, or for our national armed forces? There was peace, and peace was here to stay. The Ukraine became Ukraine.

Just as Covid gave us a rude awakening two years ago from our holiday from history, so Putin roughly shook us awake again this February. Once again, we were unprepared. Just as a pandemic left us facing unanswerable questions, so now geopolitical and religious illiteracy have left us hostage to an inscrutable doomsday man.

What had seemed past and gone for ever—pandemic, war—was very much back with us. And now that the Russians really had shown up, not quite in the Fulda Gap but still on NATO’s border, I felt the same uncertainty and fear as I did nearly forty years ago, on that Monday morning at Ossendrecht Barracks.

When we are overcome by uncertainty and fear, there’s always one defence we reach for: moral disgust. Putin was made out to be Hitler reincarnate; genocide loomed in Ukraine; and Russia had to be cancelled. Haarlem Philharmonic, as its own act of exemplary, ultimate resistance, scrapped a festival of Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky. And so it was that our own nonchalance caught up with us.

After all, if we had paid even a bit more attention, we could have known that NATO’s expansion in the late Nineties caused alarm, both in Russia and among Western diplomats. And when Putin arrived on the political scene in 1999, he consistently made it plain what dream it was that impelled him. It is the dream of the Great Russian empire, as shaped by Catherine the Great and Tsars Alexander II and III in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He reintroduced the double-headed eagle as the national emblem of church united with state, thereby proclaiming that Moscow was (after Rome and Byzantium) the Third Rome, an Eastern Orthodox state with Putin as Tsar.

Of course, we do know that “religion being appropriated as a cloak for political and military aggression” is one of the myths of our time. The trouble with myths, though, is that some people believe them—and who act accordingly. It falls to Putin, being one of those believers, to salvage old Russia’s glory by reincorporating the old stomping grounds of Kyiv and the Crimean peninsula within the Holy Russian Empire. Belief and soil sometimes unite in a sacral bond, particularly when He Who Would Be Tsar has apocalyptic thoughts of acting at one minute to midnight. In such a situation, sanctions will ultimately fail, and a major war could really be on the table. Thus, we are held hostage, the arms race is in full swing, and calamity could be just around the corner.

After my week in the study, I finally caught up on the newspapers and magazines and was pleasantly surprised to see Reformatorisch Dagblad republish a C.S. Lewis article in its magazine. It concludes: “If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things —praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts— not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.”

Words like these bespeak the confidence of faith, something we need more now than ever before.

The author teaches Social Studies at Driestar Christian University, and church history for the Seminary of the Restored Reformed Church at VU University Amsterdam. This is a translation of an article published in Reformatorisch Dagblad on March 12, 2022

Related Articles