Weekly column: In the EU, history does not exist (because it might harm you)

06-05-2022

Christian Life

Marco Gombacci, CNE.news

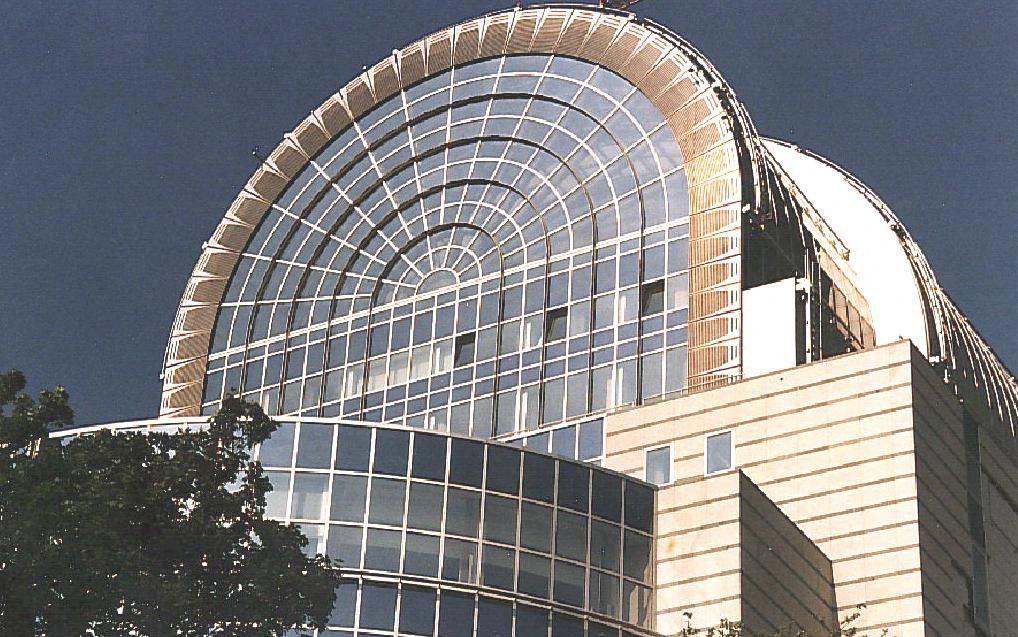

From the outside, the European Parliament in Brussels gives you the impression you are in the financial district of New York. Photo EPA

Christian Life

Have you ever been inside the European Parliament? Right upon landing at the Brussels airport, a huge banner invites you to visit the EP. It is the centre of the democracy at the heart of Europe.

And moving through the city of Brussels, you will find more panels and posters inviting you to visit the European hemicycle as if it were an absolutely unmissable experience.

On certain aspects, I might agree. If you are in Brussels, please visit the European Parliament. But perhaps not for the same reasons you would expect.

No national identity

The first time I entered the building was in 2009. Honestly, I felt excited. I arrived at Place Luxembourg, the square in front of the EU Parliament. I saw many people coming and going, looking busy on their phones. But the background of the massive glass building reflecting the light of Brussels’s (little) sun made me feel as if I was in New York City’s financial district. Not at the heart of the capital of the so-called “Old Continent.”

Marco Gombacci was born in 1985 in Trieste, Italy.

He works as EU and foreign affairs analyst. He reported about the Mosul offensive (Iraq), the battle to reconquer Raqqa, from Deir Ezzor (Syria) and Nagorno Karabakh (during the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaigian).

He authored the book “Kurdistan. Utopia di un popolo tradito” (ed. Salerno, 2019).

Opinions and articles have been published by Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, The Daily Express, TgCom45, TG5, Rai1, RaiNews 24, TRECE TV, FRANCE24, La Libre, Le Temps, and many others.

First, security control. When I walked further in the hallways, I remained disappointed. It was all grey, gloomy and cold around me. There were no signs of national identity, no symbols of local characteristics of European regions, and no paintings, pictures or memorials of the European history of nations.

Before I visited the European Parliament, I had been in the Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome, where the House of Representatives is. That is one of the most symbolic places of Italian politics. Its history starts back in 1653, when Pope Innocent X commissioned a residence to the Italian sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The rooms are embellished with ancient and modern artworks by Carlo Carrà, Giorgio De Chirico and Renato Guttuso.

Breathing history everywhere

I had also been in the House of Commons in London. The benches there were arranged using the configuration of the original St. Stephen’s Chapel’s choir stalls. They were facing one another. This arrangement facilitated an adversarial atmosphere representative of the British parliamentary approach. The distance across the floor of the house between the government and opposition benches is 13 feet (3.96 m), and is said to be equivalent to two swords’ length.

Not to mention the French Assemblée Nationale. The history of that building includes the first sitting of the Council of the Five Hundred. Its hallways and rooms recall the Versailles castle.

Those are three places where you can breathe history. Their past seduces you. You see the power of the strong identity of those countries.

Different histories are a value

This is simply the opposite in the European Parliament. When I asked my guide why the European Institution avoided showing any sign of identity in the public spaces, I received an answer that is still stuck in my mind today: “Because in this way, we don’t upset anyone.”

Unbelievable! Instead of making the different histories, cultures, and religions of European countries a value (something to be proud of), it was preferred to cancel them to delete diversities. They made everything and everyone bland as one, without giving a heart or a soul to this place.

Cancel culture came to Europe

In the following years, we have seen other attempts to cancel history. The so-called “cancel culture” arrived in Europe.

In Brussels, a movement wanted to tear down the statues of King Leopold II, guilty of being racist and of being a colonial leader. The Belgian Red Cross wanted to delete the traditional symbol of a cross not to hurt other religions. And the conventional Brussels Christmas market was renamed “Winter pleasures” to avoid using the word Christmas.

A few years ago, in Italy, a school visit to a museum in Florence was forbidden because some paintings, including Marc Chagall’s “White Crucifixion”, could hurt non-Catholic families.

Oxford University wanted to remove Homer and Virgil from the compulsory classics as part of a diversity drive. But the Iliad and the Odyssey are central works of ancient Greek literature. And Virgil’s Aeneid is one of the most revered poems in Latin literature. But these are cancelled.

In other European countries, the debate around tearing down statues, removing portraits of Christian figures or removing the crucifixes from the public sphere just started.

New identity hindered by history

All this reminded me of my missions in Iraq and Syria. I was there to report about the atrocities by the Islamic States. ISIS barbarism destroyed the ancient Roman temple of Palmyra, the historical artefacts in Ar-Raqqah and Mosul, many churches, temples and other ancient historical artefacts. They beheaded Khaled al-Asaad, a renowned antiquities scholar in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. They hung his mutilated body on a column in a main square of the historic site because he refused to reveal where valuable artefacts had been moved for safekeeping.

Why? Because removing all traces of any previous culture or civilisations is the ideal way for the group to establish its own identity and its propaganda platform so it can leave its mark on history.

We do not have to allow this to happen in Europe. We should ask the European leaders to do the opposite: open the door of our museums, show our cultural heritage, and learn from our history.

We should ask the leader of the European Parliament to adorn its hallways and rooms with pieces of art that celebrate Europe’s glorious past and celebrate its Christian-Judeo roots. Europe is not just sixty years old; it has a millennial history made by Romanisation, Christianisation, and Ancient Greek cultures’ influence.

Instead of only opening aseptic institutions, the European Union should promote the opening of our museums and churches to proudly show the world the beauties of our Western and Christian culture.

EU lacks a soul

Now, the current European Union lacks a soul. We can’t speak about Europe without recognising who we are, without recognising our Judeo-Christian roots. We should be proud of our common Judeo-Christian roots. From Palermo to Hamburg, from Bilbao to Warsaw, we have to be proud that we have something in common such as our Judeo-Christian history, identity, art and culture, which keeps us united. To learn, grow and be human beings, we need to know our culture and art to differentiate ourselves from those who want to eliminate our cultural heritage.

We are no one if we don’t know where we came from.