Florence Nightingale, inventor of modern nursing care

25-08-2022

Christian Life

Enny de Bruijn, RD

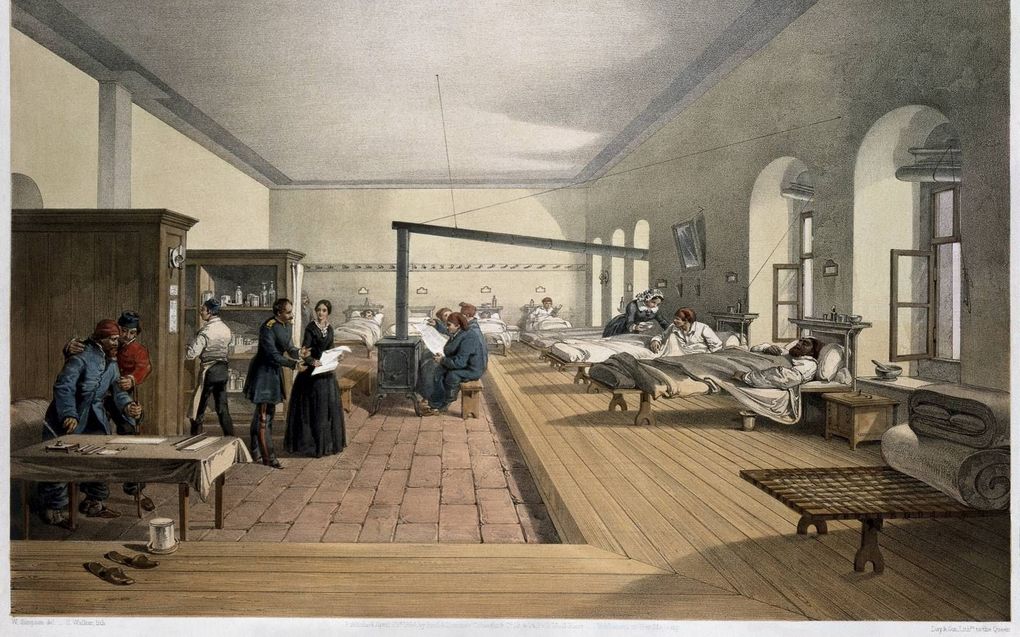

Hospital of Scutari. Photo Wikimedia

Christian Life

It might look a bit sweet, an image of Florence Nightingale in a hospital ward. You do not really see how complex and unique her life has been. She became world-famous for her work as a war nurse. But especially her talent for administrative tasks rescued countless lives.

Florence Nightingale was 34 when she and a group of nurses arrived at the hospital in Scutari (near Istanbul) in 1854 to help wounded soldiers. They had been warned, these women. But the situation was even worse than they had thought. The entire hospital was one big place of misery. Patients lay in their own excrement on beds all over the corridors. Rats scurried through the rooms, and beetles and other insects buzzed around. There was a grievous shortage of soap and bandages, and even water had to be used sparingly.

Some women would have fled from such a place screaming. But not Florence Nightingale. She rolled up her sleeves and began giving directions. She immediately sent someone to the market to purchase scrubbing brushes. With these, she put the least sick patients to work: they had to scrub the halls from floor to ceiling. She got the nurses to work taking care of the sick and organised the food supply for all people. In addition, Florence tried to get the patients to wash and change themselves and even battled the ubiquitous lice. In this way, she made the military hospital look more and more like a real hospital.

Florence Nightingale must not have been an easy-going person. She looks a bit fanatical if you look at her portrait. But that characteristic brought her a long way in life, and she sometimes needed that stubbornness. Whoever worked in the Scutari hospital could not afford to shy away from problems; she had to work hard to create order in the chaos. Despite her beautiful gown.

Silk, velvet and lace, those things were just the outside of Florence's life, reminders of the beautiful, rich girl she really should have been. But her eyes spoke another language; those were the eyes of a serious, driven woman — a woman with a calling.

Her parents must have had a lot to do with this vocation of hers. They must have wondered why they could not have had an ordinary daughter who wanted to marry a nice, wealthy man and then lead a common woman's life with a comfortable home, nice clothes, pleasant tea parties and, if necessary, some charity work. All of that was within reach. So why did Florence have to travel to faraway countries to nurse wounded soldiers under the most terrible conditions? Her mother especially did not understand.

Influential family

Money was not a problem in the British family into which Florence was born 200 years ago. Her father, William Shore, was very wealthy and had inherited a great uncle's possessions and his surname -Nightingale-. Her mother, Fanny Smith, came from an influential merchant family that had fought for the abolition of slavery.

After their marriage, William and Fanny took a grand tour of Europe. They named their two daughters after the places where they were born: Parthenope after the mythical founder of the city of Naples, Florence after the city of Florence.

Those two girls had everything that their hearts could desire. In the summer, they lived on one estate, in the winter on another. They could dress beautifully; their parents were in the best circles; they could learn whatever they wanted and marry whomever they desired.

But to Florence, the parties of mother Fanny -a born networker, fond of contacts with important and influential people- were nothing. She often felt awkward and clumsy in such gatherings and hated being in the spotlight. Clashes with her mother, who was as stubborn as she was, were inevitable. Florence, of course, did not know then how valuable those influential contacts would be later in her life in getting the things done that she deemed important. That realisation came only later.

She liked father William's lessons better. She and her sister had a governess at first, but from the age of twelve, their father took charge of their education: classical and modern languages, history, and philosophy. Florence proved to be a studious girl, and it says something about her that she loved mathematics a hundred times better than playing the piano or doing handicrafts.

Iron will

But when she was twenty and told her father that she would like to do something for society as a working woman, he was shocked. According to him, that was not the purpose of a woman's life. Her mother was even more outspoken about it: she wanted Florence to get married.

Yet William and Fanny were no match for their daughter. Florence not only had an iron will, but she also persevered, realising that God called her to help the poor and sick of the world. That is why she wanted to become a nurse. All the interesting men who proposed to her only distracted her from that goal.

Thus, already in her youth, Christianity was an essential source of inspiration for Florence. What exactly she believed has been written about all over the world. Also, in her later life, she said and wrote a lot about religion and theology. She came from a family of Unitarians (who do not believe in the Trinity), and she was certainly not a dogmatic Christian. Her faith experience was rather mystical: she heard, as she said, the voice of God through Whom she was called to a life of service. And she saw the whole world as the field of activity in which the progress of God's Kingdom had to be promoted. In very concrete terms: dressing wounds, emptying bedpans, fighting poverty and slavery, caring for the less fortunate.

The Lady with the Lamp

It is a beautiful picture, the lady with the lantern. Romantic paintings have been made of it, and even more romantic poems. Like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's verse, "Santa Filomena" (1857). A fragment:

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

And slow, as in a dream of bliss,

The speechless sufferer turns to kiss

Her shadow, as it falls

Upon the darkening walls.

As if a door in heaven should be

Opened and then closed suddenly,

The vision came and went,

The light shone and was spent.

Thanks in part to this poem, it became popular to refer to Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) as "the Lady with the Lamp". However, the image of the nurturing angel who brings comfort wherever she goes seems romanticised. According to Nightingale's biographer Mark Bostridge, she made her nightly rounds not so much out of concern for the wounded as a need to check on her staff: she was afraid that the nurses were secretly drinking with the patients - or worse.

Professional nurse

In Florence's time, being a nurse was not a comfortable, respected profession that suited her position. Often, women who could do nothing else and still had to earn money worked in the care of the sick; poor women, alcoholic women, women who did the bare minimum to make a little money and, if necessary, went to bed with the sick but did not care for their patients with heart and soul. But Florence did not want to be a nun or a deaconess; she just wanted to be a professional nurse. And for this, she had to create her own path.

When she was about 30, her parents finally agreed to her plans, and she was permitted to study in Germany. While her mother and sister (the wealthy ladies they were) took a therapeutic holiday in the spa town of Karlsbad, Florence spent three months in the training centre of the Lutheran deaconesses of Kaiserswerth. Then she did an internship in Paris at the hospital of the Roman Catholic Soeurs de la Charité. “She would never be content to be a soeur de charité”, a friend wrote about her at the time. “She would soon get tired of dressing sores. However delightful she might think it now, she would want to make all the soeurs do it better.”

Worst possible conditions

On her return to London, Florence immediately became a hospital manager for better-off ladies. These were, of course, not quite the poor people she had in mind, but the job was a start, and at least it made her name known in the right circles. She would soon find herself in a better place, for in 1854, England became involved in the Crimean War. That was the armed conflict between the Russian Empire and the French and British alliance with the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was fought mainly in Crimea, a peninsula in the Black Sea. That turned out to be the place where they needed Florence.

She was now 34 years old, had experience, and knew the right people in government. No wonder the Minister of War immediately thought of her when he was looking for someone competent to reorganise the care of wounded soldiers. Thousands of British soldiers lay in the military hospitals in Crimea and Turkey under the worst possible conditions. There was a lack of everything, but especially of staff. There was even a total lack of female nurses to care for soldiers, as the Ministry had bad experiences with women in the past. But the families of the wounded boys, back home in England, were gradually revolting. So the Minister had to do something.

Within a few days, Florence assembled a team of 38 nurses from different religious orders. With that company, she left for the war zone. The situation in the hospital of Scutari (where the wounded British soldiers ended up) was probably much more terrible than she had imagined, with all the vermin, the lack of food and medicines, and the frighteningly unhygienic conditions. But it was under these circumstances that her natural talent emerged: administration and organisation.

Thorough cleaning to decrease death toll

It was good that she was not first and foremost a caring, self-effacing nurse, who immediately went to comfort and care for the nearest pathetic soldier, but that she oversaw the battlefield like a commander and then took charge of things: the beds, the food, and the cleaning - everything needed to bring peace, cleanliness and regularity back to the infirmary.

Yet more soldiers died in her hospital than in any other. At first, she did not know why. Only when Scutari was visited by an official health commission in 1855 did it become clear that the barracks had been built on top of an open sewer. Only then were measures taken: thorough cleaning, better ventilation, disinfection of all buildings, and a proper drain. The death toll immediately dropped dramatically.

Florence must have rejoiced in this, but it must also have bothered her. Had she taken all these measures earlier, she would probably have saved thousands of soldiers' lives that were now cut off. One of her biographers, Hugh Small, even thinks she felt so guilty about it that all her later work is just one big attempt to make up for it.

Cholera and typhoid

In 1856 the war ended, and Florence Nightingale returned home. The world-famous mission to Scutari was only a brief episode in her 90-year life. However, it was an episode that determined the rest of her career. She returned with a parasitic infection that kept her ill for years and forced her to rest a great deal, but that did not prevent her from publishing one book after another, one report after another. And thousands and thousands of letters. She must have written almost as easily as she talked.

With all these texts, she became, if possible, even better known than she already was. She had not only worked as a nurse in practice but also thoroughly thought about the theory behind the profession, and she knew how to convince influential and learned men of her insights. Her penchant for mathematics came in handy here. For example, she could show exactly how important hygiene was in a hospital with hard facts and figures. Most soldiers in Scutari did not die from their war wounds but from (unnecessary) inflammations and infectious diseases, such as cholera and typhoid. To clarify this, she even invented a new kind of graph: the polar diagram.

This struggle for hygienic conditions is also reflected in the books she wrote for ordinary people, such as "Notes on Nursing", 1859. Her advice is as valid as ever: Wash your hands. Ventilate the room well. Clean the toilet well. Ensure clean water. Preventing infectious diseases is better than curing them.

Florence Nightingale became so famous that she was constantly asked to participate in official research committees. A fund was set up for real nursing training, entirely according to her ideas. Even heads of state, including the German Emperor and the Dutch Queen Sophie (wife of King William III), came to her for advice. Her work inspired Henri Dunant when founding the Red Cross in 1863. Nurses trained by her travelled the world to practice her new ideas on health care. Florence Nightingale thus became the founder of modern nursing - it was not without reason that her birthday, 12 May, was declared International Nursing Day in 1974. Even during her lifetime, she became something of a legend.

In the 90 years of her existence, she achieved more than any other woman of her generation. She was not a real feminist, but her example showed that women could also fulfil an essential and valued task in society. She died on 13 August 1910, in her sleep. Her family were offered a funeral at Westminster Abbey - an exceptional honour - but chose a simple grave in the churchyard of St Margaret's Church in East Wellow, Hampshire, with a memorial stone bearing only her initials and the dates of her birth and death.

Related Articles