Abraham Kuyper is known for many things, but first of all, he was a journalist

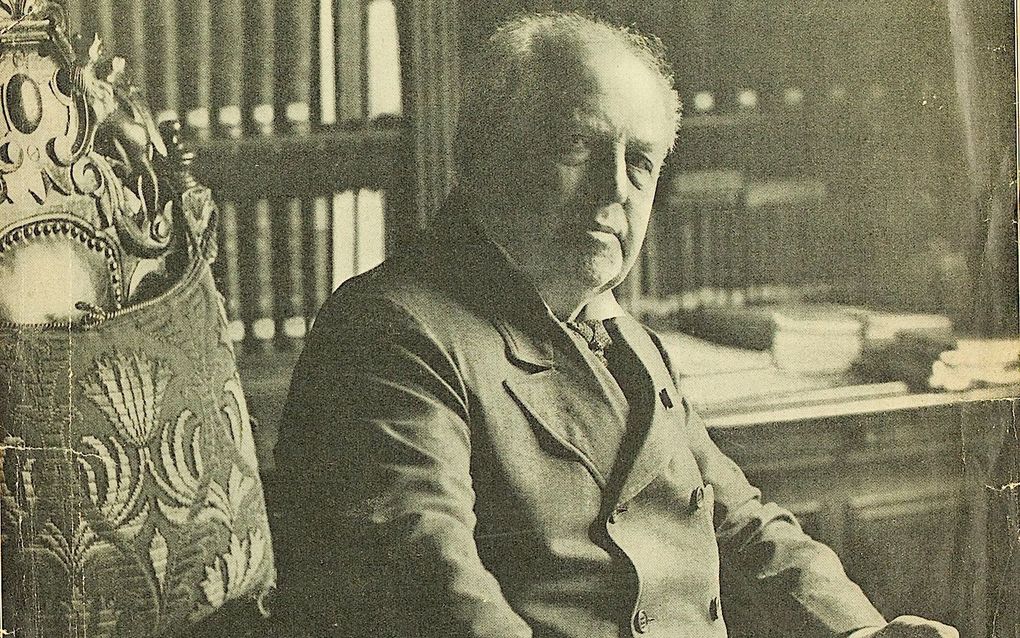

The best portrait made, Abraham Kuyper said of this one. From the cover of the Katholieke Illustratie in 1912

Christian Life

Abraham Kuyper was open-minded and international but had no problem using anti-Semitic clichés. In some churches in America, South Korea and South Africa, he is still famous. In his own country, the Netherlands, he is nearly forgotten. To prevent this, Johan Snel wrote a new biography – an alternative one.

Calvinism was an international movement for Kuyper. For that reason, he travelled a lot in Europe and was connected with the whole world. As a journalist, he wrote about all this as well.

Most people know Kuyper (1837-1920) as a theologian, a philosopher and a politician. He even served as the Dutch Prime Minister (1901-1905).

But besides all he did, he wrote for his newspaper and magazine, says Dr Johan Snel, the new biographer of Kuyper. The Dutch historian did PhD research after Kuyper as a journalist. On Thursday, he defends his thesis at Kuyper’s own Free University in Amsterdam.

“For over fifty years, he wrote from nine in the morning until half past twelve”, Snel tells. “Kuyper had an incredibly strict work schedule. If the maid came one minute early with the 11 o’clock tea, she had to wait.”

Many of the articles he produced were published in books afterwards.

Johan Snel (born 1961) always says he is a historian who wandered into journalism. He writes and lectures about journalism at the Ede Christian University of A.S. (CHE). He published books about the freedom of expression and journalist ideals. In 2020, he published a book on “The Seven Lives of Abraham Kuyper”, a biography.

So, no doubt, Abraham Kuyper was a journalist. But he did this work not without a purpose or obligation. “For him, it had the political goal to activate the famous ‘little people’”, Snel says.

During the earlier days of the Anti-Revolutionary Party, Kuyper said to Groen van Prinsterer that the movement would only flourish “if we had a paper”. Only that could mobilise the people. Snel: “So, journalism served a political goal.”

Politics, in its turn, was a means to change society. “Kuyper’s ideal was pluralism. He defended the rights of all groups in society: the Socialists, the Catholics, the Jews and also the Calvinists. As soon as you had principles, he thought you had a legitimate place in society.”

Snel does not think this pluralism was a means only to get recognition for the Calvinists. “I have read too many principled articles about this to say that. For instance, a series of sixteen articles from 1874 about the topic: Is error punishable? His conclusion is very liberal, namely that any pressure is fruitless here. I am convinced that Kuyper was a convinced pluralist.”

To publish all those ideas, Kuyper promoted the freedom of expression. “He believed in the exchange of ideas and principles. For that, he defended this freedom to a great end. Nowadays, the debate about freedom of expression concerns the right to insult. That is actually curtailing freedom because the strongest will win. Kuyper would not have defended that. But as long as it was about ideas, the freedom was almost absolute.”

Would we call him a journalist today?

“Yes. An opinion journalist. I’ve looked into the description of the present Dutch Council for Journalism. That definition of a journalist is very broad, and Kuyper would fit into that very well.”

What journalist genre did he use?

“That was, of course, the opinionated style. Research shows that this style dominated the Dutch press even until the seventies. After that, the informative style became leading.

In Kuyper’s days, reporting came up with interviews and features. But the opinionated style was the one for Kuyper.

He had several genres. His comments, for instance, the famous three-stars. They were polemic analyses about current events. But he also wrote Biblical meditations.”

Kuyper was more than just a study scholar in journalism. “During my research, I was surprised to see how much he was on top of current affairs. More than I previously thought.”

In which style did he write?

“First of all, he used very figurative language. He took these images from the daily life. And most of the time, he used them only once. We know he sometimes asked the errand boy what word to use for a thing or to check a term on the street. His son Herman once said: If you would throw my father from a tower, he would shatter into images.

He could also use archaic language. Take the expression “little people”. We connect that with Kuyper, but he took it from William of Orange in the sixteenth century, who tried to mobilise the “little people” behind him.

So, Kuyper’s style is a unique combination of archaism and street language. In those days, it was not usual for a chief editor to use informal language.”

In your thesis, you write that Kuyper did not see himself as a representative of Christian journalism. Did he not believe in Christian journalism, then?

“Indeed, he spoke about the Christian press. And he himself, he was a Christian in journalism. But Christian journalism was not a normative idea of him.

In 1895, he wrote about his idea about journalism in a series “The free word”. There, he says that authors and readers share the same values. And they interact with each other. The journalist, therefore, is not just sending, but also listening.

All papers and magazines serve a particular set of values or principles. That might be Christian principles or Socialist principles.”

How did Kuyper inform himself?

“We don’t know that so well. We never had a record of what books he had and read. We know that he got several newspapers delivered at home every day. There were both Dutch and foreign newspapers. Also, during his travels, he was reading continuously. He documented himself thoroughly.”

Given that Kuyper’s days had just 24 hours, it isn’t easy to understand how he got time for everything. One answer is the steadfast rhythm during the day. “The morning was there to write. He did that even when he was travelling for vacation. The afternoon was there to study. When he was Prime Minister, the ministerial council was moved to the afternoon because Kuyper still wrote in the morning. And every day, no matter the weather, he walked for two hours. If he had done one hour and a half in the afternoon, he did half an hour extra during the evening so that the two hours were filled.”

Lunchtime was for the family. “Then he played with his children. He showed, for instance, that he could lift all his eight children at once. But he also catechised his children. We know that he had an intimate relationship with his children continuously. Although, the whole family was structured around the father’s high calling.”

More than other Christian leaders of his time, Kuyper had a strong international orientation. “As a young man, he frequented London. There, he was introduced to Prime Minister Gladstone, the Christian-Liberal who became Kuyper’s political hero. But after the Boer War, he has never been to England again.”

After London, he got to know Paris. And when Berlin came up in the days of the German Empire, he went there as well. He even visited New York. “He visited the great world cities in their glory. He was also very fond of world exhibitions. There, he saw new discoveries and techniques.”

During his first visits to London, he bought the collected work of Edmund Burke. “He read through that when he was bedridden with flu in 1873. There, he discovered that Calvinism is an international movement. And that Calvinism was the motor of Anglo-Saxon history, both in Britain and America. The Netherlands were only a part of that international movement.”

That was a new perspective within the Anti-Revolutionary circles in which Kuyper lived. “First, the international orientation was not so common during those days. Groen van Prinsterer looked to Germany and also to France. Kuyper had a distaste for France because of its liberalism. He was much more fond of the Anglo-Saxon world.”

Did he have an international influence himself?

“Very limited. Holland was not an important country. There were not many correspondents in The Hague. When Kuyper was Prime Minister, he did attract some publicity because of the Boer War and his attempts to mediate.

Although he did not like France, he was very open to correspondents from Paris. I discovered that he did that very strategically because he knew that Paris was the centre of the press world those days. Everything printed there was read and often published in the Anglo-Saxon world the next day.”

With foreign correspondents, Kuyper spoke in French, English or German. “He was a linguistic phenomenon. French, he spoke and wrote fluently. And it is very full of images too. His English and German were at a lower level but still very high. Letters to theologians, he did in Latin. The Jews in Odessa he impressed with Hebrew. But when he tried the classical Greek in Athens, they could not understand that.”

Speaking about Hebrew: Kuyper often complained about the many Jews in the Dutch press. What was his position towards them?

“Very mixed. The Dutch Kuyper scholar Prof. George Harinck has described this best as bittersweet. He had no problem in using anti-Semitic clichés, for instance, that the Jews were too dominant in the banking and the press. On the other side, he did not have any doubt that the Jews had the same citizen rights as the others. He even stimulated them to build their own schools and so on. And personally, he was befriended with Jewish colleagues as well.”

Why is Kuyper better known and respected internationally than in the Netherlands?

“Abroad, they still remember him as a theologian. In his own country, his theological legacy is forgotten. The Reformed Churches do not exist anymore. The Christian-Democratic Party has gone down dramatically. And so on. The days of the pillarisation have gone.

What still attracts foreigners is, I think, the social commitment in his theology. He presents theology as an activating force.

I have not studied Kuyper as a theologian. My interest was the journalist. And Kuyper as a phenomenon. Because that, he was.”

Related Articles