Is Hungarian pastor's arrest matter of fraud suspicion or religious freedom?

12-03-2024

Central Europe

Alexander Faludy (in Budapest)

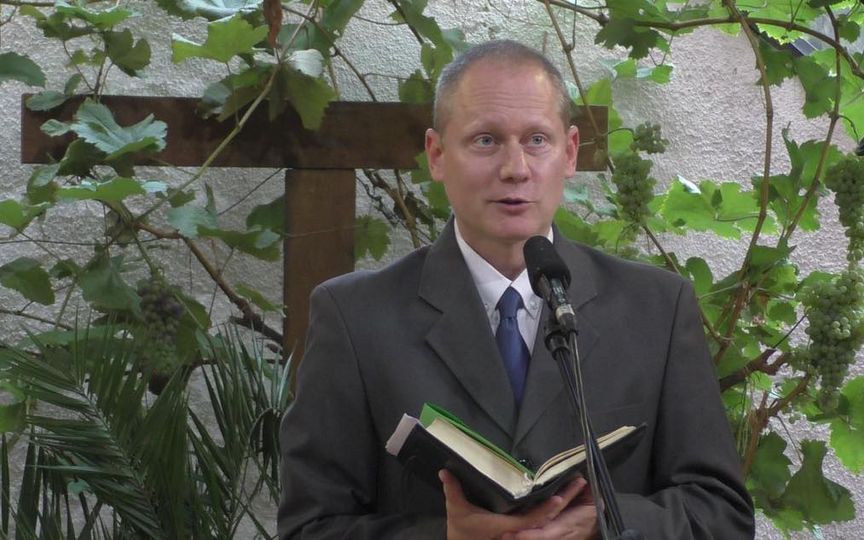

Pastor István Ónodi was arrested by the Hungarian authorities because they suspected fraud. Photo Metegyhaz.hu

Central Europe

Pastor István Ónodi might not have slept so well if he had known that his house would be turned upside down at daybreak. That early morning in February, he was arrested for fraud.

The Hungarian has been detained on suspicion of “Fraud against the State budget”. Mr. Ónodi is a pastor of the independent Methodist Magyarországi Evangéliumi Testvérközösség (MET), known internationally as the Hungarian Evangelical Fellowship (HEF).

The pastor was arrested at his home in Budapest early in the morning on Tuesday, February 20th, by officers of Hungary’s National Tax and Customs Authority (NAV), Hungarian media outlets report.

Authorities claim Mr. Ónodi committed fraud as HEF’s Chief Finance Officer through inaccurate reporting to the tax authority viz HEF’s social service institutions, operated through its charitable arm Oltalom.

According to an HEF statement, NAV officers arrived at 6 am. They conducted a 3-hour search of the family home, which Mr. Ónodi shares with his wife and two young children. Mr. Ónodi was present throughout the search but taken into custody upon completion. Sources close to HEF tell CNE that, while no items were removed, NAV officers did copy the hard drive of Mr. Ónodi’s home computer.

A statement on the Facebook page of HEF’s President, Pastor Gábor Iványi, claims Mr. Ónodi was arrested only after he declined to answer questions without his lawyer present. According to Dr. Iványi’s account, Mr. Ónodi was then made to surrender his mobile phone and was handcuffed -but remained present during the search.

CNE could not reach Mrs. Ónodi for comment.

Following the arrest, Mr Ónodi was transferred to Békéscsaba, 210 km southwest of Budapest, close to Hungary’s border with Romania. On Friday, February 23rd, he appeared before a judge in nearby Gyula, who remanded him in custody for 30 days while the investigation continued. Mr. Ónodi was represented in proceedings by his own lawyer.

A statement by Békéscsaba’s Prosecutorial Office says that it “initiated the arrest of the economic manager responsible for several church institutions, who failed to declare and pay public taxes exceeding 6.5 billion HUF [14.4 million Euros], for the crime of budget fraud causing particularly significant financial damage”.

The statement continues by saying that “according to well-founded suspicions”, Mr. Ónodi allegedly not only issued employees with pay slips showing deductions which hadn’t been made. It claims that he “submitted false returns to the competent tax authorities in relation to employment-related obligations” over a period stretching from Feb 2015 to Jan 2022”.

Prosecutors say Mr. Ónodi under-declared HEF’s liabilities for the collection of employees’ income tax and social security contributions by making returns with either “zero content or for [only] a minimum number of employees”, stating a number which didn’t reflect staffing realities at HEF institutions.

Justifying Mr. Ónodi’s ongoing detention during investigation, prosecutors claim the measure is needful because “the high penalty for the offence mean[s] that there is a risk of absconding”. They also fear Mr Ónodi could “jeopardise the effectiveness” of investigators’ data gathering “by influencing witnesses and manipulating evidence”.

In Hungary, high-value fraud against the state budget carries a prison sentence of five to ten years.

Pressure

Mr. Ónodi’s lawyer declined to answer questions from CNE without his client’s authorisation. Dr. Iványi has made a statement on behalf of HEF saying that “we stand by the innocence of István Ónodi… and will fight with all legal means to clear his name”.

HEF has previously maintained that its acknowledged problems meeting social security payments arise from the government’s failure to implement fully a 2017 European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decision mandating the return of HEF’s legal church status, lost in 2011.

The 2011 loss of status deprived HEF of monetary support available to other officially recognised churches, thereby destabilising its finances. The law also removed recognition of the Mennonites and some Pentecostal churches. HEF’s treatment, the ECtHR ruled, constituted a breach of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights concerning Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB).

Difficulties between the government and HEF have intensified since the autumn when the government cut off funding ordinarily due to HEF and other charities for providing social services. NAV (Hungary’s tax and customs authority) said it would count the funds against HEF’s social security debt.

HEF claims Mr. Ónodi’s arrest should be understood not as the outcome of an objective legal process but only the latest chapter in a campaign of official harassment. “We call on the authorities to stop the politically motivated campaign against the HEF [pursued] since 2010”, says Dr. Iványi.

Some church members have more specific criticisms: “The investigation involving MET’s finances started two years ago. It would normally have ‘timed out’ the day after István’s arrest for lack of progress”, claims HEF Comms Officer, Zsófia Vajay.

Regarding the authorities’ last-minute choice to proceed, she points to a recent political scandal as a crucial context. The latter forced the resignation of Hungary’s President, Katalin Novák, and implicated Reformed Church bishop Zoltán Balog (a former Fidesz cabinet minister). The Balog-Novak scandal, she says, means the government has an incentive to “create a distraction by “generating a negative impression of HEF”.

Church which divides

HEF broke from Hungary’s United Methodist Church in the 1970s. Before 1989, it experienced harassment from the Communist authorities, who refused its official recognition.

HEF is widely respected for its social work with vulnerable and marginalised groups in Hungary, including people with disabilities, Roma people and persons living in extreme poverty. It has, however, faced attacks from detractors who say it lacks a firm doctrinal basis.

Indeed, according to some observers, HEF’s emphasis on social work seems to define the church more than its proclamation of the Gospel or its worshipping life. Many registered members, critics allege, sign up to show symbolic support for HEF’s humanitarian work – not to participate in church life.

Dr. Iványi’s strongly left-wing political stance has also been a problem for some people. Since 1990, Dr. Iványi has consistently identified with Hungary’s left-wing parties. He sat as an SZDSZ (Liberal) party MP from 1990-94 and 1998-02.

In March 2022, he addressed the United Opposition’s closing election campaign rally in Budapest and said prayers and blessed at the event. That blurring of the spiritual and the political was uncomfortable even for some people sympathetic to HEF’s problems.

While acknowledging some of these criticisms The Rev. Dr. István Zalatnay, a Reformed pastor and university lecturer in Budapest, thinks they shouldn’t alter basic perceptions of HEF’s predicament. “I certainly wouldn’t draw the line between faith and political involvement in the same place as Gábor – but we can’t have a situation where the ability of a church to continue its life depends on how acceptable its leader is to the government”, he says.

Dr. Iványi was once a friend of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. He conducted the latter’s church marriage (1992) and baptised Mr. Orbán’s first two children. However, he’s been highly critical of Mr. Orbán’s national-conservative Fidesz government, which has been in office since 2010.

Some Christians at home and abroad admire Mr. Orbán for his pro-family policies and resistance to the modern LGBT+ movement. Still, Dr. Iványi has attacked the Prime Minister’s Christian credentials. “What he [Orbán] does is against the teachings of Christ”, he told The New York Times in 2019. “It is the exact opposite of what the Bible preaches about treating the poor, about justice, about responsible service”, he said.

Dr. Iványi criticises Mr. Orbán particularly for what he claims is hostile rhetoric towards migrants and Roma people. He also objects to provisions criminalising homelessness, which Fidesz has annexed to Hungary’s constitution.

“Favoured” churches

“I can’t comment on the specifics of the Onodi case,” says Dr. David Baer – author of a number of studies on religion in Hungary and Professor of Christian Ethics at Texas Lutheran University, “but”, he continues, “I think it’s clear that the ongoing harassment of Ivanyi’s church would not be possible if HEF hadn’t been stripped of its status in a manner that the ECtHR found to breach the European Convention on Human Rights.”

The intensive scrutiny applied to HEF seems to be very different to the approach the government takes to the accounts of officially recognised churches. In 2013, the government formally exempted favoured churches from the usual audit standards applicable to charities. In 2018, it dispensed official churches from public procurement transparency requirements.

The latter move meant that once public money was given to officially favoured churches, it became “private” money and didn’t have to be accounted for. It was a development which concerned Dr. József Péter Martin, head of the anti-corruption monitoring body Transparency International, Hungary.

“Around that time, we also saw large increases in state funding for churches”, Dr. Martin says. For him, that’s worrisome because “so much of the money seems to have been spent on construction projects -an area very vulnerable to misuse of public funds”. Yet, Dr. Martin continues, authorities have shown “a remarkable lack of curiosity” about whether the money has been spent correctly. “It’s very puzzling”, he observes.

Related Articles