Iain H. Murray, the historian who looks forward

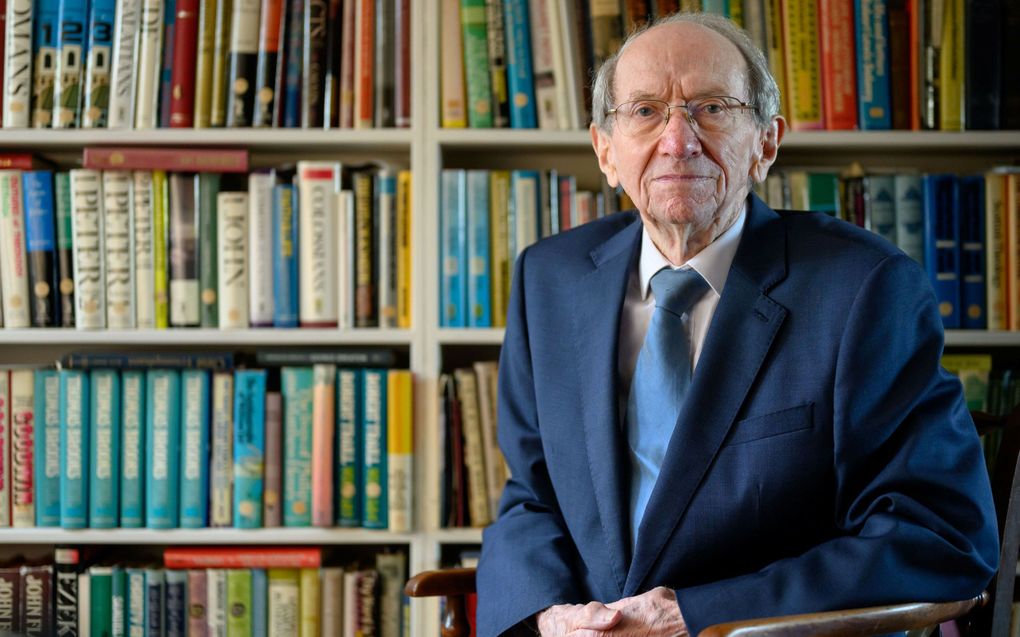

Author Iain H. Murray. Photo Ian Georgeson

Christian Life

As a boy, Iain Murray would only pick up a book on tennis. The rest didn’t bother him. The school noticed he was “far behind” with reading. Now, Iain H. Murray has become a world trademark with his stack of books and biographies from the English-speaking church history. And even at 93, he still has some works in preparation.

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

For the first time in nearly 70 years, he lives alone. Last year, his wife Jean died. In the previous 69 years, they always did everything together.

She read what he wrote before it went to print. After his retirement in the late 1990s, they were often away from home, preaching and lecturing in Australia and the United States. Together, they were happy when they returned home to their bungalow with that beautiful large garden in Colinton, a village on the outskirts of Edinburgh.

Enthusiastically, he opens the front door to me with the words. “If we were Americans, we would hug.” Neither of us is an American, but hugging we do. His hearing aid squeaks from it.

We have known each other for some time. When I lived in the Scottish capital for six months at the end of the 1990s, I met Mr Iain and Mrs Jean Murray in church on Sundays and in the prayer meeting on Wednesday evenings. And on Sunday afternoons, they regularly invited people for tea.

He had then just retired as editorial director of The Banner of Truth Trust, the publisher of Reformed and Evangelical reading material. And ministers from several countries know him from the Leicester Conferences. Along with Jean (pronounced as in “jeans”), Iain also served as host for the Banner of Truth Youth Conferences.

The garden and the house still look the same. The sloping lawn is still beautiful. The small bust of Spurgeon still stands on the windowsill.

However, enough has passed in his study. Few have written as much after retirement as he has. Partly because of Murray’s work, the history of Protestantism in English-speaking countries –and especially the revivals– is very accessible. Such a culture of biographies and chronicles hardly exists in church life elsewhere in the world.

We are here in the house you lived in with Jean for over thirty years. How is it to be on your own again?

“That’s a whole new experience. It brings you back to the foundations; we are all to leave this world alone. As long as we live, we have new things to learn. And less activity contributes to that end. There is more time to stop and pray.”

I can still see you walking hand-in-hand through Edinburgh on your way to the Wednesday night prayer meeting. As if you were friends.

“We were, for sure. As long as you’re together, you don’t realise how married life shapes you. It really is the best half that you lose when parted.

In 2015, we noticed that her health was deteriorating. Heart failure began to trouble her hindering from ascending slopes no steeper than this lawn,” says Murray, pointing outside. “In a measure, it also affected her memory. With the exception of one occasion, she always recognised me.

She died in this house on 27 March last year, on the night of Tuesday to Wednesday. She was lying on a hospital bed for the first time. On Sunday, she had last spoken. During that week, I had prayed: Lord, take her home. She was ready to go, and this last prayer was answered. Our daughter was there too.

We had already lost three of our children. Baby Andrew only lived to be four days old. Jonathan was living in Australia and complaining of headaches for some time before he died in his sleep in 2015. I clearly remember him looking well when we said goodbye after a visit that summer.

Stephen worked as a lawyer here in Edinburgh. He died of cancer in 2019. He was always a churchgoer, but little more than a year before his illness, he was transformed into a resolute Christian. They were all much loved.”

The three other children are still alive: two sons in Australia and our daughter in London. They and their partners and grandchildren are in his prayers.

He further asks in his prayers if he may finish some books. “From Jean’s hand, I have some addresses on Susannah Spurgeon, Charles’s wife. I think it is worth publishing.

Furthermore, I have Jean’s handwritten memoirs, which she has completed. I encouraged her to put her life on paper, in part because, when loved ones die, too often, hardly any witness is left for children and grandchildren.

By the way, most of the surprises after her death were not in her memoirs, but in notes, she made in her Bible and other books. I found things there about spiritual deliverances and such that I did not know before.

Jean was an active reader to the last. She had been stimulated to read from a young age and always saw that as a great blessing.”

And yourself, were you a reader from a young age?

“Very little. When I opened a book at all as a teenager, it was usually about tennis or other sports. Besides, the Second World War disrupted my school days. I went to seven different primary schools in that period, being moved about because of bombing or something. I was falling tremendously behind in both language and maths.

When I was 14, my mother said: If he doesn’t start reading now, it will be hopeless. The school they sent me to said, I was “far behind” in reading. I found that humiliating. In retrospect, it was God’s trigger.

This last school, which I went to in 1945, was for boarding pupils on the Isle of Man. My shortcomings in mathematics remained, and the only university that I could enter was Durham, provided I had passed the preliminary exams in Latin beforehand. It became a language I enjoyed.”

Conference

He had met Jean at a conference at Hildenborough Hall in Kent. “Groups of young people came there to spend a week with the Bible. It was there that I first heard that the gospel is personal and that Jesus came to suffer for individual people. I was unaware of hearing that before, although I grew up in England in a Presbyterian church. As a 17-year-old there, I came to know the Lord Jesus. And so did Jean.”

He was then at a boarding school on the Isle of Man, between England and Ireland. “Fifty years later, I went back once. I met a man there who was in the dormitory group I was supervising the year after my conversion. He reminded me that I spoke on Scripture, with exhortations, every night after “lights out” and that he had heard the gospel for the first time then. Funny, huh, how sometimes years later you hear how your work has borne fruit.”

The boarding school was Anglican. Murray thinks his housemaster was Anglo-Catholic. “At least he read the prayers. About the Dutch, he once said that he could not understand how a nation could come under the influence of something as objectionable as Calvinism. That was the first time I heard the word Calvinism, and it made me curious.”

That week at Hildenborough Hall not only brought Iain into contact with Jean. This was also where he first heard mention of Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones. “I stayed a few weeks longer to help at following conferences. To a group of staff helpers, I once said in my foolishness: Here come the best speakers from all of England. A Welsh girl countered: “No, Dr Lloyd-Jones doesn’t come here. “Then why not?” I asked. “Well, he’s a Calvinist”, she said, with no more explanation, but my curiosity was further awakened.”

So, on one free Sunday, he went to Westminster Chapel in London to hear this preacher. “It was about original sin from Psalm 51. I immediately felt the weight of it, but most of it was above me.”

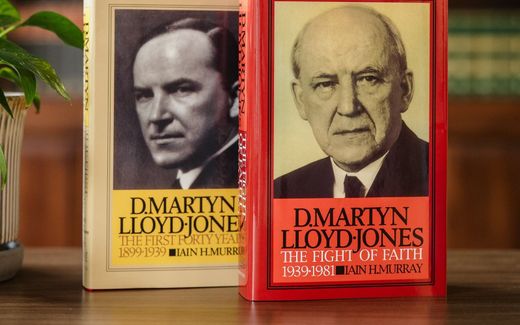

That was in August 1949. In retrospect, he understands well exactly what themes Lloyd-Jones was working on at the time. In the 1980s and 1990s, he published a two-volume biography of Lloyd-Jones.

In the autumn of 1949, the “doctor”, as he was called, spoke in Murray’s birthplace of Liverpool, in the north of England. “That was completely different from the earlier Sunday. Very accessible and evangelising. My mother was there too. This preaching touched her, and it was the start of abandoning her liberal unbelief.”

It was Lloyd-Jones who asked Murray in 1956 to lecture on church history in Westminster Chapel. Thus, his first books were born, such as The Puritan Hope and The Forgotten Spurgeon.

You have constantly been writing for decades now. Have you ever thought of retiring as an author?

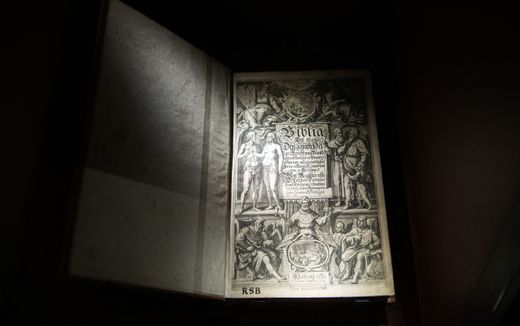

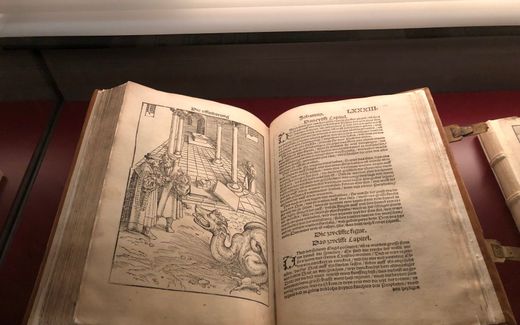

Laughs: “Haha, no. At present, I am seeking to complete what has been in hand for a while. This includes England’s Evangelicals, two volumes from 1525-1700.

Five years ago, I also started a biography on James Packer. Before 1970, we often worked together. Working on this book has been both a renewal of an old friendship and a benefit of learning more from him.

Packer later left for Canada. I met him again there in 2003, and we kept in touch until he died in 2020. He was not a man who let himself be known easily.

There are already two biographies about Packer, but I think I can add something. Among other things, the meaning of his contacts with Anglo-Catholics, and his emphasis on love and compassion for all men, including those whose doctrine, at times, we must oppose.

Some Anglo-Catholics, by the way, were faithful preachers. Spurgeon, for example, praises Henry Liddon, canon of St Paul’s Cathedral in London.” Murray picks up a volume of Sword and Trowel from the shelf to show Spurgeon defending the Scriptures as God’s word by a lengthy quote and comment from Liddon in 1890.

You have written about 40 books. Which one do you love the most?

“Haha, always the last one, writers say then. That’s the closest to your heart.

To be honest, I still get a lot of fulfilment from Revival and Revivalism from 1994. There’s a lot of importance in it which is too little known. Evangelicalism Divided, a controversial book from 2000. It has been given a wide readership and won friends beyond anything I anticipated.”

You have written many biographies yourself. Could you imagine someone writing a book about yourself?

“Well, you can’t stop anyone. I myself have done something of that kind, which needs a final chapter. But I don’t count it a priority. The only hope is that it will encourage younger preachers and others to consider the Christian ministry as a most privileged office and influential calling.”

Your name became almost synonymous with the Puritan heritage. Were you brought up with this?

“Oh no, definitely not. I was converted under a preaching closer to fundamentalism, although of the best kind.

After my conversion, a woman from our home church near Liverpool gave me an old booklet: the Westminster Confession. I had never heard of it, even though our church was Presbyterian. My father did remember just a few quotations from the Shorter Catechism he had heard in childhood. But what a marvellous document this Westminster Confession and Catechism is! I believe the Banner of Truth Trust would send the Catechism to anyone who asked for one.

When I was deployed as a soldier to Malaya in 1950, my mother sent me Calvin’s Institutes. My thinking was beginning to change regarding the grace of God that makes us His own. But then already, things had begun to change.”

Jumper

We had arranged twice. On the first day, Murray was wearing a nice warm jumper. On the second afternoon, when the photographer joined us, he was in a suit such as he would wear in the pulpit on a Sunday.

The photographer’s Nikon cameras catch Murray’s attention. Son James is a director for Nikon in Sydney. As a small boy, James was already interested in cameras. So, the camera type number goes on a note for Australia.

He doesn’t actually like photographing in his study, as so many books and papers are lying around. “My wife would never have allowed visitors in it,” he says.

To the untrained eye, everything is mixed up here: old and new, thick and thin, dark and brightly coloured. The shelves bow under the collected works of old writers: Goodwin, Edwards, and Manton. More than anything else, this is Iain H. Murray’s engine room as an author. On top of the shelf is a black-and-white photograph of young Jean.

One of the secrets is the notebooks with an archive of what he has gone through. “It is very important that you record what you read. In 1960, I started taking notes somewhere on a white page, as it was a book of my own. And otherwise in a notebook.

When I talked to Lloyd-Jones, I often made notes afterwards. When it became clear in 2015 that Jean’s health was deteriorating, I wrote down things she said. I am thankful now that I did. John Flavel was right to say, “My memory never yet failed me because I never yet trusted it.” Those notes are invaluable."

In 2014, you gave me a book by Archibald G. Brown as a gift, in which you wrote: We need to pray for such preaching today. Why?

“Brown’s preaching is very direct. He does not read a manuscript from the pulpit but speaks directly to you, looking at you. There is genuine empathy and feeling in it.

In addition, Brown was a true evangelist. He spoke about sin and grace, about being lost and being saved. His preaching was more than instruction. There was heart appeal in it and in his praying. I think we miss that today.”

What are you: Scottish or English?

“I’m a mixture. I was born in England. And my education and culture are shaped by that. I still watch the news through the English BBC and not the Scottish, although I live in the Scottish capital.

I am sad at the Scots’ antagonism toward Calvinism. The English have forgotten much of the best of their past. For the Scots, it is still close, and unregenerate hearts have no love of the word of God, which is still remembered.

But my genes are Scottish; my parents belonged here. In the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014, I voted no. I was very much against it. The gospel once did much to forge a unity between the two nations after long hostility between them.”

And then, recently, your driving licence was withdrawn. How is that for you?

“Oh, don’t put that in print. That is such a blow for me. I love the countryside, and I am only a few miles away from it. I feel so sad that I can’t go where I want anymore. My whole life, I never had a car accident. I think the doctor may have taken this decision too abruptly. Perhaps I should have questioned. I would be happy to have permission to drive just 4 or 5 miles from home.”

Is it a lesson in acceptance of growing old?

Hesitantly: “Yes, it is. Until I was 92, I was fit, but now I must make changes. But there are new blessings for Christians in age. If God keeps us here, it is for a purpose. The reality of Christian friendships is wonderful, including the influence of prayer. We are all in training for the world to come, and the meaning of that becomes more evident to us.”

In a newsletter you distributed via email, you once wrote: We now have more friends in heaven than on earth.

“That is certainly true. The older we get, the more the number grows. I do not doubt the saints in glory know much about what is happening here. But in the knowledge they now enjoy, they see the purposes of God leading to the resurrection and all things under Christ. What is still dark to us now will soon be bright.

All those friends in heaven – it’s hard to imagine, isn’t it, but it also gives so much to look forward to.”

Biography Iain H. Murray

Rev. Iain Hamish Murray (born in Liverpool in 1931) is a minister and author. As a conscript soldier, he was deployed with the British Army to Malaya (in present-day Malaysia) in 1950.

After his return in 1955, he married Jean Ann Walters and became a pastor in England. From 1956, he was assistant to Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones at Westminster Chapel in London. During this period, his lifelong involvement in the church history of English-speaking countries began. He produced about 40 titles on church history and biographies, mainly of the Puritan heritage. From the beginning, he was also involved in the Reformed publishing house, The Banner of Truth Trust. From 1981 to 1991, he served as a pastor in Sydney, Australia. Sermons and lectures by Murray can be found on YouTube and Sermonaudio.com. Iain and Jean had six children, three of whom died. Murray has been a widower since March 2024.

This article was made in cooperation with the Dutch Reformatorisch Dagblad.

Related Articles