Paying to kill a child for fun? It happened in Sarajevo, and it can happen again

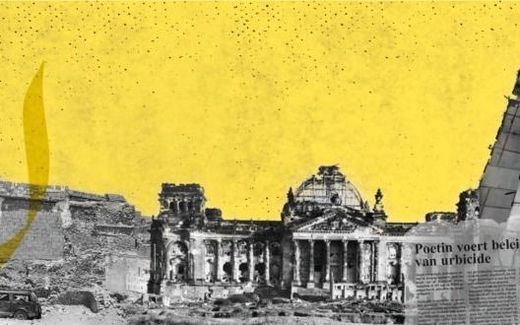

Civilians run for their life as they are targeted by snipers in Sarajevo. Photo AFP

Christian Life

When Mirela Popaja read about the so-called “safaris” to the besieged city of Sarajevo, she immediately saw herself again as a child in wartime. Was our columnist ever a target of the rich snipers that came to kill Sarajevans?

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, we thought that our pain had healed by now, except that it hasn't. In the past weeks, we were shaken by a revelation that reopened the wound. During the siege of Sarajevo between 1992 and 1995, wealthy foreign nationals allegedly paid to shoot at civilians from the hills above the city alongside Serb forces.

The 2022 documentary, also titled Sarajevo Safari, by Slovenian director Miran Zupanić, compiled testimonies claiming that wealthy foreigners paid to shoot civilians from Serb-controlled positions around Sarajevo during the siege. A safari where the prey was human, where a civilian life could be purchased for entertainment.

Reports suggest participants came from several countries, including the United States, Russia, and Italy. The documentary revealed that some paid the equivalent of 100,000 euros for the experience, with different prices allegedly set for shooting a man, a woman, or a child. More than 11,000 Sarajevans died in those four years.

Exposure

When I read this news, my reaction was immediate, not intellectual, but physical. My body knew before my mind could form language. My stomach tightened, nausea washed over me, and I could feel the blood leave my face. I sensed danger, exposure, as if the city around me had once again lost its walls. I was no longer an adult reading a newspaper. I was a child in wartime Sarajevo, living in a world where water, electricity, and safety were luxuries that were scarce. Where the sound of shelling replaced conversation, and where crossing the street was a calculated risk between life and death.

Was I ever a target in someone’s private game?

And a question rose in me: Was I ever a target in someone’s private game? Was my mother? My baby brother? My neighbours? The children I played with?

The horror is not simply that people were killed. It is that someone, somewhere, paid to do it. It was leisure. A thrill. An experience.

Empathy

Today, I am a therapist. I cannot read such revelations without holding them in both hands. The hand of memory and the hand of reflection. One holds the pain of lived experience; the other searches for meaning, for what this reveals about human beings and what we are capable of when empathy fails.

What disturbs me most is not only the violence, but the psychological distance required to make such an act possible. To hunt a human being “for fun”, one must strip them of personhood. One must reduce them to an object. A body without a story, without a mother, without a history, and without a future.

Albert Einstein once said: “I believe that the horrifying deterioration of the ethical conduct of people today springs from the mechanisation and dehumanisation of our lives.”

Safety

First, we stop seeing each other. Then we stop feeling each other's emotions. And after that, anything is possible.

In therapy, I often witness how trauma distorts perception, how fear can turn a person inward, severing them from connection. But while trauma erases empathy as a defence, privilege can remove empathy as indulgence. Safety unexamined becomes carelessness; power without reflection becomes cruelty.

The Sarajevo Safari is a story of what humans become when empathy breaks.

The Sarajevo Safari is not a story of war alone. It is a story of what humans become when empathy breaks. And empathy breaks slowly. Not in one moment, but slowly, brewing each time we label someone other or decide some lives matter less. Each time we silence, mock, exclude, or erase.

Contact

As a Gestalt practitioner, I focus on the present moment and often return to the idea of contact. War is the ultimate aftermath of broken contact. Sarajevo Safari was its extreme mutation.

However, healing happens when we turn toward each other and meet the other. Not as an object, not as a symbol, but as a living human with a nervous system that trembles like ours, with a pulse that quickens with fear and expands with joy. When we witness, feel, and stay present, healing happens. And it does not when we turn away.

As I think of Sarajevo today, I see its cafés alive, its streets noisy, its people charmingly stubborn and full of laughter. Yet beneath that life, there are memories, not only of suffering but of survival. These recollections ask us to remain awake. To refuse numbness. To refuse the seduction of distance that makes another human disposable.

Because the conditions that create a safari are still present in the world. We see them when refugees are treated like floods, not families. Or women with cancer are spoken of as burdens, not as humans in pain. When communities are judged by faith, skin, identity, or history. When a child in Gaza, Ukraine, Congo, or Sudan becomes a number instead of a name.

Eyes

Empathy vanishes when we stop looking each other in the eyes. Eyes that are the ultimate proof of the divine in us, made in God’s image, Imago Dei. And empathy returns when we choose to look, to acknowledge the endless value of the other.

My hope is not to reopen wounds, but to keep them from closing in silence. To honour those who lived, those who died, and those who are still healing. To remind myself, and perhaps others, that the line between hunter and human is thinner than we want to believe.

The Sarajevo Safari is a warning, but also an invitation. To never stop looking at each other in the eyes. To keep choosing empathy, even when the voices urging us to shut down are loud. The opposite of dehumanisation is contact. And contact is how we survive.

Related Articles