A faith festival builds bridges in city full of tensions

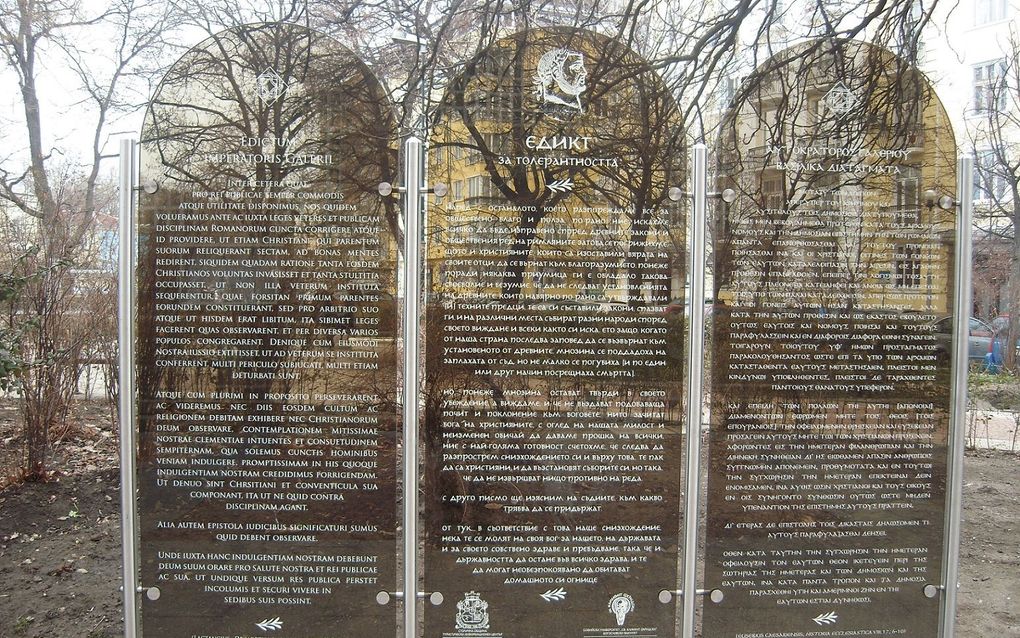

Trilingual plaque in Latin, Bulgarian, and Greek with the Edict of Serdica in front of “St. Sofia” Church. Photo Wikipedia, Мико

Opinion

It was a pleasant August evening. Under the cover of midnight darkness, a young couple approached the Sofia Central Synagogue and sprayed the numbers “14/88” on its wall. Right under these digits, with a much thicker pink paint, they attempted to draw a flipped swastika. Afterwards, the boy and the girl, their faces covered with Covid masks, swiftly disappeared into the night.

This is no just vandalism, but an anti-Semitic message. The 14/88 is a white supremacist digit. And the swastika is the infamous Nazi symbol.

Bulgarian historians have long boasted about the preservation of thousands of Jews during the Second World War. But now, the country sees a notable surge of ethnic-based hate during the past decades. Incidents include daubing of offensive graffiti on monuments or breaking of headstones in cemeteries. Hate speech and vandalism have been spreading tangibly: from football gangs spraying swastikas onto Gypsy homes and Turkish mosques, to Protestant gatherings being singled out for coronavirus dissemination, and lately, to hammering pickaxes into cars with Ukrainian registration plates.

Vlady Raichinov (1974) is translator of both fiction and theological literature. He is a member of the Union of Bulgarian Journalists, co-hosts a radio program, and writes articles.

He presides over the Bulgarian Evangelical Society, publisher of "Zornitsa" – the oldest Bulgarian newspaper that has been in print since 1871.

In December 2014, Vlady was ordained as a minister with the Bulgarian Baptist Union and is currently serving in the pastors' team of First Baptist Church, Sofia. He is also vice president of the Bulgarian Evangelical Alliance.

Vlady and his wife Katya parent a beautiful pre-schooler named Maria.

Since the turn of the century, nationalistic political figures have used TV studios and social media to stir up racist sentiments. In its annual report on religious freedom, published two weeks ago, the US Office of International Religious Freedom described several spikes in anti-minority attitude: “In October, vice presidential candidate Elena Guncheva of the Vazrazhdane Party referred on social media to local politicians of Jewish and Turkish origin, saying they should consider themselves “guests” in the country.” In February, a Bulgarian MEP gestured what appeared to be a Nazi salute in the plenary chamber of the European Parliament, claiming he was simply waving good-bye to the speaker. In addition to political figures posing under the guise of “patriots” while spewing straightforward hatred towards people of non-Bulgarian origin, the report goes on to describe incidents like defacing memorial plaques, death-chanting against Muslims and usage of xenophobic speech during Bulgaria’s three Parliamentary election campaigns in 2021.

Bulgarian publishers recklessly reprint literature by Hitler, Goebbels or Jürgen Graf, and such materials can be found in most bookshops and street stalls. Of course, this promotes models of thought that are easily picked up by racially motivated gangs. In September 2019, the Bulgaria-England football qualifier was halted twice as a group of some fifty young men with shaved heads and black hoodies put up a supremacist show including racist scanning, political fascist gestures and monkey chanting.

Sofia and Its Square of Religious Tolerance

However, this has not always been the case. The capital of Bulgaria takes a special credit with its heritage of peaceful religious co-existence. Only within a couple of square kilometres in the very centre of Sofia, one can find a number of holy sites devoted to various faith groups. Orthodox, Catholics, Muslims, Protestants and Jews profess their faith openly, without fear or tensions. Evidence of this is the so-called “Square of Religious Tolerance” in the heart of the city, where houses of prayer are located within walking distance of each other.

Within about one hour of casual walk, one can visit several rather different types of religious establishments: Eastern Orthodox churches of “St. Nedelya” and “St. Petka”; “Banya Bashi” mosque; “St. Joseph” Roman Catholic cathedral; Sofia Central Synagogue; several Protestant churches (Methodist, Congregational, Pentecostal); Romanian Orthodox Church of “St. Trinity”, Armenian Apostolic Church of “St. Mary”, Russian Orthodox church of “St. Nikolay”, among others.

The proximity of all these sites of religious importance issues an important message: the capital of Bulgaria is a safe place not just for peaceful co-existence but also of mutual respect. Faith groups have partnered for hundreds of years in building a welcoming and reliable public square where no one is ostracized or hated.

Annual Festival of Faiths

In recent years, an additional expression of mutual respect and public partnership is built through a unique formation that has brought together Protestants, Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Armenians and (sometimes) Orthodox spiritual leaders: the National Council of Religious Communities. NCRC is an advisory body that summons representatives of six major faith groups for regular talks. The Council organises joint events and expresses common positions on religious issues, such as legislative proposals or political statements specifically related to religiously fuelled vandalism.

This year, for the 7th time, NCRC organized a “Festival of Religions”. Peace, unity, tolerance, diversity – those words were repeated by faith leaders in the centre of Sofia. In a world with swirling warlike passions and reckless hate talk, bridges like this are more than necessary.

“The meaning of this festival is to celebrate tolerance and good will,” said Robert Djerassi, chairman of NCRC and president of the Jewish organization “Shalom” in an opening ceremony in May. Professor Garabed Minesyan of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church added: “Everyone should live as they see fit, but always with respect for their neighbours who profess a different worldview.”

According to Hairi Emin, a representative of the Muslim community, “the meaning of this festival is mutual understanding and tolerance, which contribute for public peace.” Former deputy grand mufti Birali Mumun stressed that it “shows both our differences, as well as our willingness to stand together.”

“The Council functions on basic values embedded in Bulgarian society and formed by several faith traditions. We are able to live together and understand each other, and thus overcome the fear of our differences and get along,” said Bulgarian Evangelical Alliance secretary Greta Ganeva. “Bulgaria has rich traditions in this respect. We work together, we laugh together, our lives are connected. Everyone has their own uniqueness, but this bouquet of cultures is a national wealth.”

The festival included an art exhibition by Balin Mollov, whose paintings depicted key religious sites in Sofia, as well as historic buildings associated with them. A Turkish folklore ensemble presented dances and songs, and Sofia Gospel Choir performed a beautiful bouquet of Protestant hymn tradition. The annual event has a special place in the city’s cultural program and has served as an opportunity of mutual awareness and reduction of religious tension.

Edict of Galerius on Religious Tolerance

As a site of tolerance, Sofia indeed possesses a centuries-old tradition. Under a previous name, Serdica, this city was the birthplace of a unique document: the so called “Edict of Serdica” issued by emperor Galerius on April 30, 311.

Predating the famous Edict of Milan (313), the decree was published within days before Galerius died, officially ending Diocletian-inspired persecution against followers of Jesus Christ in the Eastern Roman Empire. With its proclamation that “they may again be Christians and may hold their conventicles, provided they do nothing contrary to good order,” the Edict of Serdica may well be one of the first governmental documents in human history declaring religious tolerance as a social value.

With a rich cultural background like this and a sustainable tradition of interfaith dialogue and mutual social respect, Bulgaria’s capital may actually be paving the road to a possible solution to racial hatred and ethnic tension. Religious groups may have varying ideas of what happens in the afterlife, but when it comes to the public square, we all walk on equal ground.

Related Articles