Beware of the Russian bear when it is embarrassed

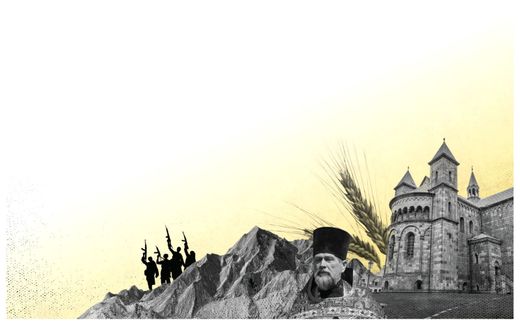

Photo RD, Corné van der Horst

Opinion

War and honour go hand in hand. At first sight, that seems to be strange. There is nothing honourable in destructing a city like Mariupol or killing civilians on the streets of a town like Bucha.

Yet, the concept of honour is never far away on the battlefield. Just look at the many high awards countries grant for victories won in battles; for example, the Medal of Honour in the United States and the prestigious Military Willems-Order in the Netherlands.

If honour is so essential for the West already, then this certainly applies to the East. A massive but valuable theory in anthropology differentiates between cultures of guilt versus innocence, embarrassment versus honour and fear versus power.

Many Western countries are traditionally typical guilt cultures. Even though the culture of embarrassment is progressing, the idea of guilt does not seem to disappear quickly. The theology of reconciliation through satisfaction has developed the strongest in Europe. That is not for nothing. Only by admitting of and satisfying justice for the wrongdoing can the state of innocence be recovered. So, when someone is caught stealing money, the perpetrator has to admit his guilt explicitly and take care of compensation.

Most civilisations in the Middle East and Asia are typical embarrassment cultures. Parents do not teach children that stealing money makes them guilty but that it disgraces them, which is reflected in the rest of the family. It is not primarily the state of innocence that needs to be restored but the honour that must be saved. The person that stole money does not admit to having done so. However, he does meekly undergo his punishment, an implicit sign of guilt.

And last, especially in parts of Africa, the negative emotion that is felt the deepest is not guilt or shame but fear. For example, fear of evil forces. Here, many efforts are focused on the liberation of those fears. In this case, someone who stole money will do everything to contribute to a fast recovery of his peace and freedom.

Differences in dealing with conflicts

These three primary cultures are seen in how people experience their faith. But also in conflicts and wars. There has been interesting research about how American Presidents dealt with conflicts. The results? That depends strongly on where a President is from. The South of the United States is a typical society with a culture of embarrassment. At the same time, the North is a culture of guilt. Southern Presidents are, therefore, much busier with their honour and reputation. To protect these values, they are twice as likely to use violence in conflicts with other states. Those conflicts end in American victory – the restoration of honour – three times as often.

Because the war in Ukraine has been ongoing for more than a hundred days, the question arises where Russia – especially Putin – is located in this spectre of guilt, shame and fear. Does Russia have a culture of embarrassment? The answers differ – is that not logical in such a large country that knows so many internal differences?

Yet, Russia is characterised more by a culture of embarrassment than by a culture of guilt. That is already seen in famous Russian literature, with the classical work "Crime and Punishment" by Fjodor Dostojevski on top of the list. The book may have existed for a long time under the name of "Guilt and penalty", but focuses on the fact that the protagonist – who killed someone – does not feel guilt but is consumed by shame.

There are countless other stories, classical and modern, about the role of honour and shame in Russian society, especially in the countryside. A girl that marries honourably causes her family to have a good name. A boy who fulfils his military duty with honour can count on society's respect.

The Russia-born political scientist Andrei Tsygankov argues that honour is the key term in Russian international relations – not only now, but already since the tsarist era. If Russian leaders have the feeling that their honour is recognised, they cooperate with the West, he says. If that does not happen – and currently it most certainly does not – then Russia will respond fiercer, Tsygankov argues.

That insight is extra relevant at this time when after more than a hundred days, the war has not delivered what Putin expected it to. Russia has had to deal with many setbacks.

Putin might feel forced to respond fiercer

In a culture of embarrassment and honour, you have to offer the person responsible for the setbacks a way to leave the battlefield with a raised head. It is essential to prevent the scenario in which the Russian bear feels so embarrassed that he does not see a way out and takes irreversible decisions. It is unrealistic to expect a leader from such a culture to react as guiltily as Germany after the Second World War.

Because NATO members send more and more weapons to Ukraine, it is not strange to expect that Putin feels forced to respond fiercer. From the perspective of embarrassment and honour, it seems unlikely that Putin will retreat soon, even less that he will give up the conquered territories in southern and eastern Ukraine.

Partly because of that, this war has the potential to drag on for years as a frozen conflict. There will be no clear winner, but – and that is even more important in a culture of embarrassment – no outspoken loser either.

Related Articles