Christians speak out on Europe’s demographic future

Children assisted by their parents and volunteers take part in the Little Cyclists Parade during the International Children's Day in downtown Bucharest, Romania. Photo EPA, Robert Ghement

European Union

When 25-year-old Moushir Youssef came to study in the Netherlands, he noticed something different.

As a Christian from Cairo, Egypt, he no longer saw the familiar scenes of families with their many children behind them. Instead, couples walked with few or no children. Back in his homeland, this phenomenon sparked rumours. Fertility or marriage problems would often be assumed for not having children.

“It’s extremely rare to not have siblings,” he said.

He also came across another sighting while studying hydraulic engineering in Delft. In Egypt, children had a place in family life. They also tended to stick closer together as a unit. Here, family seemed like a distant concept, often marred by divorce or separation of parents.

“You get the impression that families are not connected in the West and more so in the East,” he said.

Downward spiral

Youssef’s observations reflect a deeper demographic problem that has haunted Europe for decades. According to data in the Demographic Outlook for the European Union from 2022 and Eurostat, more people from the EU’s 27 Member States are living longer but having no children or not nearly as many as in decades past.

While the overall population grew from 354.5 million in 1960 to 447.7 million in 2020, the annual number of live births continued to shrink. In 1960, it was 6.69 million and in 2020, it was at 4.04 million. Eurostat’s projections indicate that the overall population will plateau at 525 million in 2044 before hitting a downward spiral of 416.1 million by 2100. Along with that, median ages will continue to rise. Italy will be the first to have an average median age of 50 by 2030. By 2070, the median age in Poland will be 52.6 years and 52.6 years in Italy.

Statistics point to a shrinking Europe with low live births and rising median ages. However, its population problems lie within its total fertility rate. As published in the EPRS research pamphlet in 2022, the total fertility rate is defined as the “mean number of children who would be born to a woman during her lifetime.” Total fertility rates are also quantified based on the “age-specific fertility rates” for a woman in her childbearing years. While low fertility rates are a contemporary talking point, they have continued their downward trend since the mid-1960s. When looking at the issue worldwide, the World Economic Forum reported in 2022 that fertility rates have decreased worldwide by as much as 50 percent in the last 70 years.

Gender roles

In the mid-1970s, the average total fertility rate was above 2.1 births per woman across the EU-27, with 3.78 births in Ireland and 1.98 in Estonia. Fertility figures kept declining until 2005 when the rate became 1.47 in that year and then 1.57 in 2010. That number currently stands at 1.53 as of 2019. The reasons for these declining rates vary. As reported by the Bureau of National Economic Research (NBER), more Western Europeans are having children later and desire fewer of them than in decades past. Socioeconomic factors also play a role. “Rigidities in the labour market,” shifting gender roles, as well as the absence of childcare have also been cited.

Europe’s demographic crisis can also be seen across the generations. The ERPS illustrated this in the shape of a pyramid. The top echelons reflect the older age cohorts that are living longer, while the lower levels indicate decreasing fertility rates. Looking closer at the generations, the Baby Boomers (born between 1946-1960) and Generation X (1965-1980) enjoyed high fertility rates while the Millennials (1981-1996) and Generation Z (1997-2012) are having far fewer children. The result has led to “a population bulge,” where the two older age groups continue to move up the pyramid as they age. This European “bulge” will only get bigger with time, which is bound to create irreversible economic consequences across the continent.

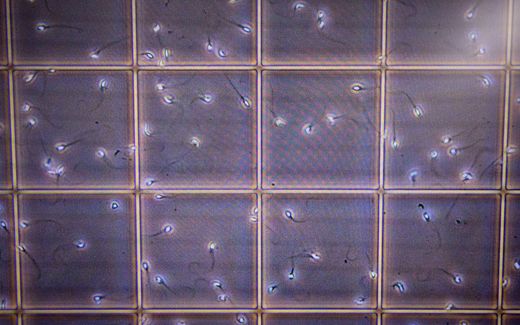

For Europe’s younger generations, having more children may not be a long-term answer, as infertility is also on the rise. Statistics from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology indicate that almost half (25 million) of the 48 million worldwide are experiencing infertility in Europe.

Responsibility

But for now, getting back to Jesus’ teachings is the key to valuing the family again, according to some Christian Millennials and Generation Zers.

“I think we have a big responsibility to stand up for our beliefs,” said Vincent Klassens, who is a Dutch native and a mechanical engineer. “The combination of influences from abroad through, for example immigration, coupled with the felt necessity to be tolerant, means that the original Dutch culture based on Christian values is put to the background, or even set aside completely in our country.”

He also says that as Christians and as a country, turning back to God with unshakable faith is essential amid a national identity crisis.

Godly family structure

For Moushir Youssef, the Netherlands needs a priority shift. Emphasising sexual pleasure over starting a family is leading many couples to forego children, he says. Rather, teaching Godly family structure may be a small but crucial step in remedying the demographic crisis.

“Teaching the value of proper Christ-like relationships and family is an important thing,” he said.

According to Mattijs Otten, a drone company owner and member of an international church in Delft, staying true to God's design and order is paramount.

“When Christians model their families in accordance with God's Word, this will set an example for society. And as being fruitful is part of marriage, having children should naturally be a desire the parents have, and a blessing God gives to the family. That might go against our society, where pressure on natural gender roles and the value of marriage increasingly diminish the worth of having children and the time parents set apart for them. This might mean being Christian will clash more and more with society, but in the end, we do not fight with the weapons of this world, and it is Gods command to stand strong in faith,” he said.

Related Articles