How to live with the evil other

16-12-2023

Opinion

Jacob Hoekman, RD

Photo Corné van der Horst

Opinion

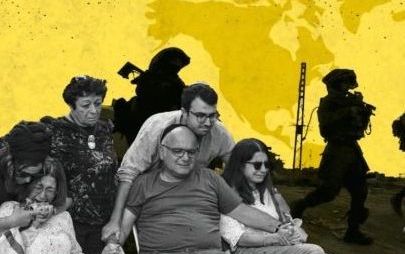

New details from eyewitnesses in recent days shed more light on the events of October 7 in Israel. They are fierce accounts, full of blood, murderousness and sexual crimes. Hamas fighters went on a rampage in unprecedented fashion.

Those who take in those details understand even better that "October 7" has caused national trauma in Israel.

At the same time, intensive bombing of Gaza resumed this week. After several days of calm, it is once again dismembered children and distraught parents that fill the screens and do not disappear from the retinas. The bizarre thing is that you can hear exactly the same thing from both sides: whoever does these things is no longer human. That person must be Satan in person.

I find it difficult how to deal with this. Can this be true? And, at a level deeper: why do I find it important that the other person is no longer classified as human?

Holocaust

While I was looking for answers, someone pointed me to Leuven theologian Prof Didier Pollefeyt. Who has done extensive research on what many people see as the ultimate evil: the Holocaust.

Pollefeyt discovered that historically there are at least three ways of looking at the perpetrator: through diabolisation, trivialisation and ethicisation. Diabolisation –or demonisation– is the most obvious one, and exactly the means that is in abundance in the war between Israel and Hamas. You could say that you de-humanise the other in order to survive yourself. The picture that emerges then is black and white: the perpetrator, by virtue of his intrinsic badness, chose to behave diabolically.

In any case, what you cannot say about this way of looking at things is that it is relativistic. Like: well, there are always two sides, and they will both be guilty. On the contrary, people who dehumanise the opponent do so on the basis of pure moral indignation about evil. And that is good, Pollefeyt believes. Moral indignation is allowed and even must have a place. According to him, that indignation is the necessary starting point of any ethics.

Mass murders

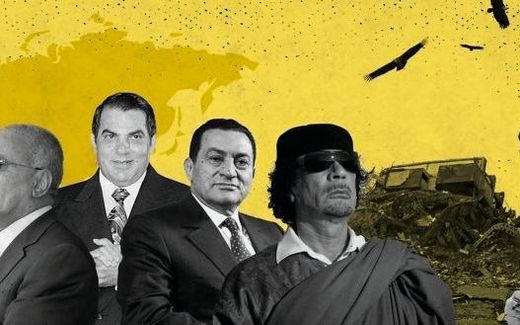

The great danger of this is that you end up in a vicious circle because there is no way to come together. To stay with the Holocaust, the Nazis saw the Jews as the embodiment of evil. "Whoever knows the Jews knows the devil," Hiter once said. Conversely, exactly the same was true. The Nazis, who were capable of these mass murders, were diabolic creatures without a shred of humanity, others argued.

Replace Nazis with Hamas, and you see the same dynamic today – from two sides. The other is utter evil, and I have no part in it. In this paradigm, the only solution is basically that the other ceases to exist. That the other is eradicated.

Obedience

But this is not the only way to look at perpetrators. The second approach is that of the banalisation of evil – a paradigm made popular at the hands of Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt. She studied the trial of Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann and found that Eichmann was not a devil at all. On the contrary, he was remarkably ordinary. That was the staggering thing for her: that people, in all their banality, can apparently contribute to the realisation of ultimate evil simply by doing their jobs. "My guilt is my obedience," Eichmann himself said.

One of the criticisms Arendt received was that, with those glasses on, she overprotects the perpetrator. "He can't help it either; he is simply part of the system now and only does what he is told to do."

No good and evil

So you can reduce perpetrators of evil to devils (diabolisation), you can see them as will-less parts of a system (trivialisation), but you can also put them in perspective. This is what the third approach, that of ethicisation, does. It is an approach that many Nazis applied to themselves during and after the Holocaust. They were driven by good ideals, they stressed, such as patriotism, civic duty, loyalty and duty ethics. The Holocaust does not contrast with these at all; rather, it is the consequence of those ideals.

As bizarre as that sounds, it is this approach that you now hear quite often from the Palestinian side. It is the approach that says, "What did you think? After so many years of occupation, isn't it logical that something should happen? That Hamas exists is thanks to Israel itself." The major drawback of this is clear: there is no longer right and wrong. Everything becomes relative, everything has to do with the bigger picture, and nothing is evil in itself.

Framework

There are three approaches, but also three problems. How do we move forward? Perhaps the biggest problem is that none of the approaches allows for forgiveness, for reconciliation and for restoration. After all, you don't reconcile with the devil. And if the perpetrator does not recognise his guilt, like Eichmann, there is little to forgive. If the perpetrator is even convinced from his relativistic framework that he did the right thing, you don't get anywhere at all.

Pollefeyt also reflected on this. He comes up with additions to the paradigms mentioned and formulates conditions that must be met before reparation and reconciliation are possible. The victim must learn to see through his indignation and thus recognise that the perpetrator has basically the same weaknesses as himself. The perpetrator, in turn, must acknowledge the suffering, admit his part in it, try to repair the damage and prevent it from happening again.

Conclusions

This all sounds nice, but there is no one who believes that this process, in the middle of a war, will take serious shape in Israel and Gaza.

And yet. It can be done. Indeed, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission has shown this before. That is seen internationally as a great success; the commission's lengthy work paved the way forward.

South Africa under apartheid and Israel today –with short-sighted conclusions– are often compared. Usually, these are comparisons that do not hold up well because the situations are so different. But if a comparison is to be made, let it be this: the success of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission will one day also be the success of Israel and the Palestinians.

Related Articles