Gloria was a surrogate mother: I felt used like a slave

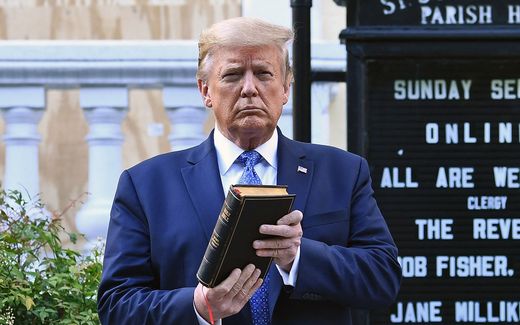

“You only hear the bright side of surrogacy, but in the end, you are little more than a slave to these agencies”, says Gloria Ruiz, a former surrogate. Photo Getty Images.

European Union

Gloria Ruiz had had three pregnancies, but nothing could have prepared her for her fourth. A traumatising seven months ended in the hospital, where she was admitted in critical condition. “I almost lost my life and the child.”

It was not Ruiz’s child she nearly lost. The 33-year-old was a surrogate mother, and she would relinquish the child after birth. “It seemed so nice; I could help someone realise their dream,” Ruiz, who resides in Temecula, California, says.

Every year, thousands of women in California give birth to children for someone else. Countries like Ukraine and Georgia offer cheaper alternatives, but the United States, specifically California, gives intended parents a well-organised alternative in a Western environment. Such a regulated environment is, however, not necessarily an improvement for surrogate mothers.

Military

Ruiz works at a school now, but in 2019, she had trouble finding a job. “My husband works in the military, so we move quite often,” she says. "I also have a son with special needs, for whom I have to be at home.”

Therefore, surrogacy seemed like a good option to her. Ruiz got the idea through advertisements on social media, she says. “I think I am in the targeted demographic: a stay-at-home mom with a stable family situation,” she says. “The idea resonated with me: you help a couple realise their dream, and you make a little extra money as well.”

In California, surrogate mothers usually earn between 45,000 and 60,000 dollars for a first surrogacy pregnancy. If a surrogate mother decides to start another surrogate pregnancy after her first, her earnings will increase. When complications during pregnancy arise, such as damaged organs, the contract provides financial compensation for this, as Ruiz’s contract, shared with CNE.news, shows.

Difficult

Kallie Fell is the executive director of the educational nonprofit Center for Bioethics and Culture Network (CBC). This organisation opposes surrogacy and wants to educate people on this topic. Fell says it is difficult to determine precisely how many surrogate mothers are active in California. “Surrogacy in the US is not federally regulated, and nobody keeps track of these women.”

This lack of tracking is problematic for Fell, who is also a perinatal nurse. “When you have high blood pressure in your pregnancy, you are more inclined to have it later in life too”, she says. “But we are not tracking these women through their surrogacy pregnancies, and we are not seeing any long-term data of the impact of surrogacy on their bodies.”

According to Fell, there is not a big taboo on surrogacy in California. On the contrary: “It is celebrated to be a surrogate”, she says. “People think giving a family a baby is a great way to help. Advertisements from the industry emphasise this.”

Ruiz sees that surrogacy is becoming more common in California. “Not everyone says they are surrogate mothers, but I did. Otherwise, you get questions afterwards about where your baby went.”

Supportive

Ruiz’s husband was not as enthusiastic about a surrogate pregnancy as she was. But he was supportive in her search for a suitable job, she says. “I figured if it wasn’t for me, I could always withdraw from the process.”

When you apply to become a surrogate, there are certain conditions you have to meet, Ruiz says. “You must have previously given birth, be financially stable, and undergo psychological screening.”

While there is not much research on surrogate mothers, the CBC conducted a study on the risks of a surrogate pregnancy compared to a spontaneous pregnancy. The results showed that surrogates were more likely to have a high-risk pregnancy. “A surrogate pregnancy had three times higher odds of resulting in a caesarean section and was five times more likely to deliver at an earlier gestational age.”

Furthermore, “women in this study were significantly more likely to experience postpartum depression following the delivery of surrogate children than after delivering their non-surrogate children.”

But that was not all that stood out: the study also found out that “women’s economic disadvantage was a major contributor to the decision to proceed with surrogacy.” While most women were not necessarily poor, they were in the lower tiers of economic strength, CBC’s Kallie Fell says. “Overwhelmingly, women reported using the payment they received to get out of debt or pay bills.”

Fell noticed that most surrogates her team interviewed wanted to proceed with a surrogate pregnancy to help other families. “That was their personal motivation”, she says. “However, when asked about other surrogates, most women said that they expected money to be the key factor in the decision to go ahead with a surrogacy.”

The screening before the surrogate pregnancy was not an issue for Ruiz. Not long after, the California-based surrogacy agency she worked with, International Surrogacy Center (ISC), matched her with a gay couple from Spain, where surrogacy is illegal. The pregnancy went well, and in February 2020, she gave birth to a boy. “I was very open with my kids about this. I did not want them to get any ideas that that was my baby.”

Four years later, Ruiz is still in touch with the family. “I do not feel like a mother to this child but more like an aunt. I know he gets a lot of love from the family, which was important to me; I need to know that this child was not just bought but is loved.”

Guilt

Ruiz says that within three months after the delivery, the surrogacy agency ISC contacted her again. “They know you are emotional and miss the baby,” she says. “They try to almost guilt you into doing it again: Did it not feel amazing to help a family like that?”

Through social media, ISC advises waiting at least six months after giving birth to apply for a surrogacy pregnancy. The California-based surrogacy agency declined to answer questions from CNE.news.

Ruiz decides to give in and start another surrogacy pregnancy, but she has conditions: “All my appointments needed to be in my city, and I wanted to give birth in the hospital of my choosing.”

In July 2021, the 33-year-old gets matched with a couple living in the US. The intended father is Spanish again.

After people from China and France, Spanish citizens make the most use of surrogate mothers in the US, research shows. The percentage of international intended parents is steadily growing each year. Despite a ban on commercial surrogacy in most European countries, there is not much a state can do when the intended parents arrive back home with a child. When a court must decide on the child's custody, a judge often goes along with the intended parents’ wishes because they believe it is in the child’s best interest.

Between Ruiz and the intended parents, everything seems to be going well. Signing the contracts is a formality. The conditions Ruiz put up before signing the contract, such as the hospital where she wants to give birth, are not included in the contract. “Looking back, I was extremely naïve to sign that contract”, she says. “I did not assume that things could go so bad, considering my first experience with surrogacy. But in the second pregnancy, nothing was the same.”

Explicit

After signing the contracts, the relationship between Ruiz and the intended parents turns sour. “At embryo transfer day, the father made inappropriate, explicit comments, and I was mortified. They did not seem to care about me or the process.”

When the intended parents say they are only interested in the child if it is a girl, Ruiz, a mother of two boys, worries about the child’s future. “It felt so completely wrong. It made me feel that this whole pregnancy was a joke to them.”

Ruiz shares her concerns with a case worker from the surrogacy agency. But the latter waves away the objections, warning Gloria of the risks of a breach of contract, Ruiz says.

Backing out of the agreement is no longer an option, says Ruiz. “At first, the agency gave me the impression that you have choices and can stand up for yourself. But you cannot do that without legal and financial ramifications. And lawyers do not want to have anything to do with this. There is nobody to defend you.”

CBC’s Kallie Fell also sees that surrogate mothers are in a legally vulnerable situation. “It is a lot of work for a lawyer, with little return”, she says. “I am not saying they should not do it, but going against Big Fertility is like a David and Goliath fight.”

Nausea

The pregnancy is a nightmare for Ruiz. She gets diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum, a type of nausea and vomiting that leads to dehydration and weight loss. “Because things went bad so fast, I hid the pregnancy from my children. But I was no longer the mom they were used to having”, Ruiz says. “I was just this person throwing up all the time, laying on her bed.”

At 28 weeks, twelve weeks early, Ruiz enters pre-term labour. “I had to get steroid shots to get the baby’s lungs to develop.” The mother makes it to 32 weeks but then faces heavy bleeding. She is rushed to an emergency hospital where she wants to give birth. There, they refuse her. “They said: You are not our patient. We haven’t seen you this entire pregnancy. We have no idea what your history is.”

Then, Ruiz is rushed to another hospital, which is the hospital the intended parents want her to be. “There I was, bleeding out, in a hospital an hour away from my home. My kids and my husband were prohibited from visiting me because of Covid guidelines.”

The doctors do not know what is causing the bleeding. Ruiz has to stay in the hospital indefinitely. “The doctors wanted me to have this baby at 37 weeks, but I was not able to wait five more weeks.”

After speaking with her lawyer, Ruiz decides to leave the hospital. “My placenta was rupturing, which meant that if things went wrong, both the child and I could die in seconds.”

The critical situation makes it possible for Ruiz to return to the emergency hospital she initially wanted to give birth. There, she deliveres a boy.

But the intended parents are nowhere to be found.

“As a surrogate, it is your responsibility to inform the intended parents that you are in labour”, Ruiz says. “But after I contacted them through WhatsApp, I did not hear anything back from them.”

The medical team assisting Ruiz decides the child will be placed in the nursery until the intended parents arrive.

Sometime after giving birth, a nurse enters her room somewhat timidly, Gloria says. “She had a post-it note for me. It read: ‘Thank you’. That was all I heard from the intended parents.”

The contract allows Ruiz to spend one hour with the baby she delivered. But the intended parents refuse to comply. “Because I was in the hospital for quite some time, they feared I contracted viruses”, she says. “In the end, I was okay with not meeting the child. I was so over it.”

Therapy

The surrogacy process is over, but Ruiz and her family still struggle with the effects of the surrogacy pregnancy daily. “Me and my children are in therapy, and I am on antidepressants,” she says. “I am terrified to be pregnant again.”

The surrogacy pregnancy also impacted Ruiz’s marriage. “My husband distanced himself from me during the pregnancy because the chances of me dying were so high.” The couple is still together, but according to Ruiz, her marriage went “through the wringer” thanks to surrogacy.

Ruiz wants to warn other women about the practice of surrogacy through social media. “You only hear the bright side of surrogacy, but in the end, you are little more than a slave to these agencies,” she says. “Women who speak out against this get harassed by agencies and the general public.”

Ruiz also got her fair share of this while sharing her story. “People say that I should not be selling my children or should not have signed the contract in the first place.”

Whereas Ruiz was previously sympathetic to surrogacy, her experiences have completely twisted her views. “My doubts arose after the second pregnancy began,” she says. “The more I read about it, the more I saw that these agencies essentially traffic people. You have no rights as a surrogate. And to me, that equals slavery.”

Related Articles