Today, I choose to belong to the Good News

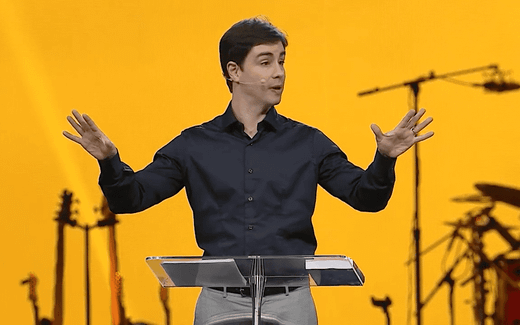

Photo CNE

Opinion

Good news is no news. That is what cynical journalists say. But for a Christian, this is not all, says pastor René Breuel in his first CNE column.

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

Every day, the first choice I face is: do I start my morning with reflection, prayer, and Scripture, or do I reach out to my phone? Do I ground my soul in timeless wisdom or in the latest developments? Do I place my frailty in an overarching story of redemption? Or do I expose myself to political conflicts, celebrity gossip, the ups and downs of the stock market, and a steady stream of tragedies and scandals?

I often succumb to the phone and let it set an anxious tone to my day. Recently, I woke up to the news that a boyfriend had set his girlfriend on fire and that a French husband had drugged his wife and invited more than 50 men to rape her while she was unconscious. In shock, I realised I had chosen to expose my heart to the world’s latest bad news instead of Jesus’s ancient Good News.

The philosopher Georg Hegel affirmed that societies can be considered “modern” when the news takes the place of religion as people’s main reference point. They grant newspapers reality-shaping authority. They listen to the radio instead of morning devotions while driving to work. They conclude the day with newscasts and television programs. Instead of attending church, they visit museums, parks, or theatres on Sundays.

The result is that our modern societies are efficient and up-to-date. However, they are also characterised by what Max Weber called a “poverty of soul and spirit.”

Character formation

In The Tech-Wise Family, journalist Andy Crouch reports that 65 per cent of American parents affirm that technology and social media makes it harder to raise children today, compared to previous generations. It is parents’ leading concern, above worries that the world is more dangerous (as reported by 52 per cent of parents), financial factors (26 per cent), or bullying at school (20 per cent)

Crouch also reports that technology makes the character formation of adults more challenging. According to the same research (which was conducted by the Barna Group):

In what ways has technology made your life more difficult?

- 42 per cent: I waste a lot of time

- 40 per cent: I’m more distracted

- 25 per cent: my devices sometimes separate me from other people

- 23 per cent: I feel like I can never disconnect

- 21 per cent: it seems like my attention span is shorter

- 18 per cent: I feel less productive

- 14 per cent: I feel anxious when I’m not with my phone

- 13 per cent: it tethers me to my job even when I’m not there

- 10 per cent: it has affected my relationships in negative ways

- 20 per cent: it hasn’t made my life more difficult

Our landscape saturated by technology presents distinctive challenges to moral formation. People find it harder to quiet their souls and tune off the noise. Their attention spans shorten. Their brains become used to constant stimuli. They become ethically desensitised and find it easier to justify bad behaviour. If newspapers regularly report horrendous crimes, losing patience with our loved ones doesn’t feel so bad, does it?

Space for the eternal

The transformation from Good News-based societies to bad news-shaped societies also presents distinctive challenges to spiritual formation. Devout Christians may read Scripture, pray, and attend church faithfully, but don’t we spend more time being formed by our screens? According to Timothy Keller,

The challenges of formation in such a digital culture are considerable. Our traditional models of biblical and spiritual formation through just a few hours of public worship time and a community group are insufficient for countering the impact of 24/7 digital technology throughout the week. Our models of theological formation give us a firm grasp of biblical doctrine, which is indispensable. Still, they fail to deconstruct culture’s beliefs and provide better, Christian answers to the questions of the late modern human heart.

On a personal level, I started to think of my day as a unit of time which can be shaped by the world’s deformation or set aside for spiritual formation. For instance, I decided to reach out to my phone only after I had spent time with the Lord in the mornings. I also started taking mental breaks without screens to go outside, let my mind rest and get in touch with my emotions for a few minutes. Before, I used to take breaks to check my phone or read the news on my computer and return to work, mentally exhausted and emotionally numb.

In the evening, I’ve found it helpful to enjoy the quiet, be with my family, and write down my thoughts in a diary. Reflecting on questions like, “What did I face today? What emotions do I need to understand better?” is a way of intentionally processing my day instead of outsourcing the management of my emotions to entertainment or letting them reappear in the form of dreams.

Psalm 23 describes quiet waters, green pastures, and soul refreshment – to those who stop and let the Lord by their shepherds (Psalm 23-13). Similarly, the prophet Isaiah declares,

This is what the Sovereign Lord, the Holy One of Israel, says:

‘In repentance and rest is your salvation,

in quietness and trust is your strength,

but you would have none of it.’ (Isaiah 30:15)

In a world of relentless bad news, to remain people of the Good News is an immense privilege. That’s who I choose to be today.

René Breuel is the author of The Paradox of Happiness and the founding pastor of Hopera, a church in Rome. He has a Master of Divinity from Regent College, Vancouver, and a Master of Studies in Creative Writing from Oxford University. You can learn more about his work at renebreuel.org.

Related Articles