Look how Down Syndrome pregnancies are increasing in EU

Down Syndrome births are continuing to decline throughout Europe. Photo AFP, Dominique Faget

European Union

Is the pregnancy test positive? Many women hope that the next nine months will come without challenges. However, that is only sometimes the case. What do you do if Down knocks at the door?

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

Several EU countries have seen a spike in positive Down (or trisomy 21) tests. Amid this increase, many women are choosing to abort their trisomy 21 pregnancy, leading to a sharp drop in live births. Not only has this caused controversial discourse on designer babies, but it has prompted questions about the tests themselves.

Out of the 5.2 million births in the EU each year, the EU Commission reports that approximately 2,5 per cent (or 104,000) are born with foetal abnormalities. In 1990, Down Syndrome accounted for 16 per 10,000 births. In 2015, that figure rose to an average of 23 throughout Europe.

The spike in Down Syndrome pregnancies has also seen an upward trend in the Nordic states. In Sweden, the EU Commission reported that the number of Down Syndrome births jumped to over 36 per 10,000 total births in the period between 2010 and 2014. No data was given for Sweden before that time. In Finland, the numbers also increased from 16-25.9 in 1995-1999 to 26-35.9 per 10,000 births in the period 2010-2014.

The Norwegian Medical Birth Register recorded that the number of those pregnancies after the twelfth week has increased from 61 per cent in 2021 to 77 per cent in 2022, according to Dagen. Vart Land cited previous data, where up to 90 per cent in the country opt for termination in trisomy 21 pregnancies. In 2023, only 21 per cent or 47 out of 222 became live births when the foetus had a congenital abnormality.

Brita Storlund, a communications adviser at the Swedish pro-life organisation Människovärde, is aware of the statistical increase in Down Syndrome in Sweden.

She says that most Swedish women opt for an abortion as soon as the tests are positive for a chromosomal abnormality or a trisomy. Storlund told CNE that exceptions do exist and mentioned a woman who did give birth to a baby with Down Syndrome. Doctors told the mother that it would be better to abort the pregnancy because the foetus would likely face heart problems after birth. Amid her doctor's warning, she decided to keep her trisomy 21 baby and later gave birth to a healthy daughter.

Storlund mentions that parents often feel they need more information when they get the diagnosis and are sometimes not given a brochure. When a woman does decide to keep her Down Syndrome pregnancy, support is available both within the private and public sectors. Some of those services include temporary housing and special outings to movies or ballgames, often arranged by volunteers. Schools and colleges offering special education programmes are widespread throughout the country.

Yet, she notes that much needs to be done to ensure women have the proper support so abortion does not become the norm in trisomy 21 pregnancies. "We should stop discriminating before they are born," she says.

Looking outside of the Nordics, some EU countries are seeing more abortions after a woman receives terrible news about a congenital abnormality. In an Exaudi report, more than 83 per cent of babies in Spain have been aborted in cases when Down Syndrome or trisomy 21 had been confirmed in the years, 2011-2015. It also cited research revealing that selective abortions continue to remain high throughout Southern Europe (72 per cent), the Nordics (51 per cent), and Eastern Europe (38 per cent).

As for Iceland, close to 100 per cent choose to have a termination in the event of a positive test for Trisomy 21, as cited by CBS. While Down Syndrome has not been eliminated, as some reports suggest, not more than two babies are born with the condition there each year.

While many women are opting for abortions after a trisomy 21 diagnosis, some may ask, why are Down Syndrome cases rising? Bart-Jan Noorlander offers an answer, who is a father, a policy adviser and a personal services consultant at the Dutch organisation, Helpende Handen. Helpende Handen (or Helping Hands) is a Dutch Reformed group that supports those with disabilities and their families.

Noorlander explains that more women are having children at a later age, particularly after 35 years old. Women who are over 35 years old have an increased risk of having a child with Down Syndrome or another congenital abnormality.

Most of all, more rigorous screenings, such as the Non-Invasive Pregnancy Test (NIPT), are better accessed and have increased in the last decade, Noorlander points out. The NIPT test helps detect trisomic conditions such as Down Syndrome.

Noorlander is correct about the increase in testing throughout the Netherlands and Europe. The academic journal the Scandinavian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology on NIPT testing throughout Europe revealed that the percentage of women using NIPT is between 25-50 per cent in the Netherlands. The NIPT test is used to detect chromosomal abnormalities during the tenth week of pregnancy.

That proportion has risen throughout many European countries, especially in Belgium, where the testing rate is above 75 per cent. Many EU states offer testing for three trisomies, including trisomy 21. Still, the journal also says that a few other EU countries allow testing for more extensive issues through genome-wide screening.

Noorlander is aware of these tests when it comes to his own family. In his wife's sixth pregnancy, water was found between the neck and brain, a sign that the developing foetus may have a chromosomal abnormality such as Down Syndrome. After some recommended testing, the doctor confirmed that the probability of having a baby with trisomy 21 was very likely.

Has the rise in testing led to more selective abortions in those with Down Syndrome? Dr Maurike de Groot-van der Mooren, a Dutch-based paediatrician-neonatologist, says yes and no. She said to Reformatorisch Dagblad last year that the decline in live births associated with trisomy 21 cannot be pinned down to a specific test such as the NIPT. Instead, advanced maternal age, as well as more frequent and accurate prenatal testing, are driving factors.

As in the case of the Netherlands, De Groot-van der Mooren noted that many women choose to abort in 85 per cent of instances where the testing shows Down Syndrome in the pregnancy.

For Noorlander and his wife's pregnancy, they have chosen to trust God because God gives life, he says. The Netherlands has come a long way in supporting those with disabilities. As an example, he cites the UN Convention on Disability, which outlines that those with disabilities have and should enjoy equal rights in all societal aspects.

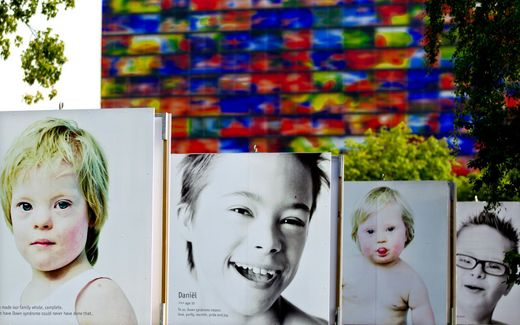

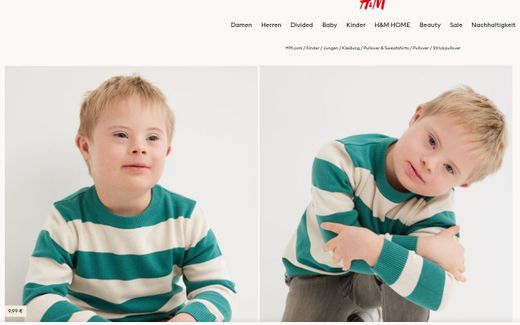

In recent years, various TV programmes and advertisements have featured children with Down Syndrome, but an overly optimistic image does not fully reflect reality, he says. At the same time, he believes that a good support network and a positive media portrayal may motivate women to keep their trisomy 21 pregnancies.

"Every person is a creature of God and therefore worthy of protection. It is important not to neglect their needs. We have to look at the disability and what they need."

Related Articles