How war monuments do more than just provoke sorrow

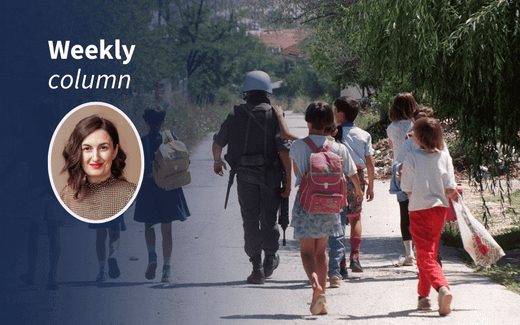

Descendants of the deceased gather in front of Bogdan Bogdanović's concrete flower. The monument is a memorial to those who were killed at the Jasenovac concentration camp during World War II. Photo AFP, Damir Sencar, canva.com

Christian Life

Monuments are meant to help us remember and heal. But sometimes, they are part of the problem again. And what do we do then if they do not help in preventing cycles of violence?

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

Across former Yugoslavia, thousands of monuments were built in the aftermath of the Second World War, mostly during the 1960s and 70s. They were erected to mark the atrocities of war and serve as a collective vow of “never again.”

Perhaps the most powerful among them is the Stone Flower in Jasenovac, one of the ten largest concentration camps in Europe. The camp, built by the Independent State of Croatia and operated by the Ustasha regime, an ally of Nazi Germany, was a site of unimaginable cruelty. Its victims were predominantly Serbs, Jews, Roma, and anyone who dared to resist.

The monument’s architect, Bogdan Bogdanović, did not want to depict horror. Instead, he designed something poetic, a flower made of concrete, opening gently into the sky. His goal was to create a symbol of beauty and gentleness. He said his message was an appeal: not to inherit violence from generation to generation, but to build peace.

And yet, he embedded a quiet but powerful reminder of suffering. On a summer day, if a visitor stands in the centre of the structure, the temperature rises noticeably. It becomes stifling and evoking a feeling of being inside a furnace. A visceral echo of the hell experienced by the victims.

Humility

Metaphorically, the monument invites us to feel with the victims, to stand beneath tons of concrete, in silence, and take a vow that we will never again allow such horrors to happen. It is a space that asks for humility and remembrance. And when art is done well, it can be transformative. It can carry memory and offer healing. But the monument didn’t stop the violence.

When war broke out again in Yugoslavia in the 1990s, many of these wartime memorials were destroyed or left to decay. Their messages of “never again” were ignored or erased.

And as I visit these places today, I often wonder: Are these structures truly a good way to remember? Or are they just something we build after war, because we need to mark the trauma, even if we don’t fully face it? What does it take to break the cycle of violence? How do we move beyond revenge?

The war in Bosnia in the 1990s brought back camps, brought back torture, and ended in genocide, in Srebrenica. Today, we too have a symbol: a white flower, worn every July 11th to mark the Day of Remembrance for the victims of Srebrenica. It represents the Mothers of Srebrenica, standing in a circle around a green coffin, mourning their sons, husbands, brothers.

But once again, a familiar pattern emerges. Every year, politicians gather in Potočari to give speeches. And while some words are meaningful, they can feel like political theatre, designed more to evoke emotion than to open space for genuine healing. Just like the monuments of the past, symbols are again tangled with propaganda.

In Tito’s Yugoslavia, monuments were often built to honour those who died for “Brotherhood and Unity.” But they were also politicised, to glorify sacrifice, to tell the story of how “we fought the Enemy and survived together,” under the leadership of Marshall Tito. The memorials became stages for a specific narrative: that we were moral winners.

What was missing was space for pain. We never really sat with our grief. We didn’t acknowledge the fatherless, the motherless, the childless. Furthermore, we didn’t speak of the families erased completely, or those left behind as shadows of who they once were. We didn’t name the trauma. We skipped over mourning and jumped straight into myth making. And so, the cycle continued. Srebrenica happened.

Now, we have new flowers, new rituals. But again, we risk missing the deeper point. The symbolism becomes ceremonial, political, even performative. What we still lack is a collective willingness to grieve. To truly feel the pain of what happened. To name it, not for a camera or a crowd, but for ourselves.

So I keep asking: Can memory help us heal, or does it entrap us in the past? Can we learn to mourn, not just once a year, but as a way of being more human? Can we build monuments that invite not only remembrance but transformation?

Are we, as human beings, capable of standing inside the belly of a concrete flower, feeling what it is like to live in a world where revenge takes centre stage and choosing instead a different path?

That, to me, is the real work of remembrance. Not just to look back. But to feel fully. To grieve honestly. And then to choose, again and again, not to continue the cycle.

Related Articles