Even in secular Czechia, Jan Hus remains popular as ever

04-07-2025

Central Europe

Jitka Evanova, CNE.news

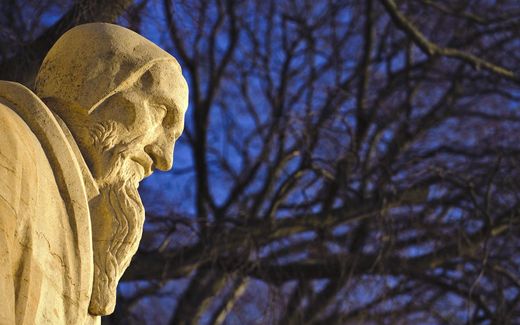

Jan Hus during the Council of Constance. Photo RD

Central Europe

Even though Czechia is a secular country, many people still know the important reformer Jan Hus. This is why.

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

Lipany was the name of the play we went to see with our kids recently. It told a story about belief and superstition, power play and expensive indulgences, and finally, the Battle of the Hussite Wars near a village called Lipany.

The full auditorium of children and adults had a great time. Sometimes, they were scared, and one of the youngest viewers once had to cry.

The (fictional) villager in the play longed for the kingdom of God and joined the preaching of Master Jan Hus with thousands of others. He listened to the preaching of this Roman Catholic priest, Czech medieval religious thinker, university teacher, rector and reformer.

This year marks the 610th anniversary of his violent death.

Hus criticised the indulgences as well as the moral decay of the Church and called for reforms. The result? He was convicted at the Council of Constance in 1415 and burned. This year marks the 610th anniversary of his violent death. Czechia still has Jan Hus Day on July 6th.

Schoolboy

Jan Hus has not passed on the stories of his childhood. We do not know much about him as a little boy, but he later wrote that as a schoolboy, he had in mind the idea of becoming a priest. “To have a good home and clothing, and to be respected by the people.”

Hus was born to poor parents in the small village of Husinec in southern Bohemia around 1370. That was during the reign of Charles IV, who was not only a German king and King of Bohemia but also the Holy Roman Emperor.

During the 32 years of his reign, Charles made the Czech kingdom a Central European power. Under his rule, Prague became the political and cultural centre and eventually the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. With about 35,000 inhabitants from various nations, it was one of the largest metropolises in Europe at the time.

Hus was a diligent student, although he did not shy away from any student amusements.

What did Charles do to promote Prague? In 1348, he founded the first university in Central Europe to compete with Paris and Bologna. Originally, it had four faculties: theology, liberal arts, law, and medicine. The university hosted many scholars from all over the Empire. At its peak, there were 5,000-7,000 foreign students, about a fifth of Prague’s population. In addition to many landmark buildings, Charles founded the New City of Prague. With many churches and monasteries, this was to be a manifestation of the heavenly Jerusalem and a new Rome.

No wonder this city made an enormous impression on young Hus. He came there to study at the university around 1385. He still had the goal of becoming a priest. For this, he was a diligent student, although he did not shy away from any student amusements: he drank, sang, danced, and loved chess and expensive clothes.

Entering priesthood

After receiving his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, he was ordained a priest around 1400 and started preaching in the church of St. Michael. Already in 1402, he moved to the private Bethlehem Chapel. It could accommodate up to 3,000 listeners from all social classes, making Hus visible to the whole city. He preached twice a day in Czech and talked not only about the reforms of the Church but also asked for deeds. He was popular, even with King Wenceslas IV and the Archbishop of Prague.

Hus lived in Central Europe. But still, he was familiar with the writings of the English Oxford professor John Wycliffe. Wycliffe’s 24 doctrines were condemned by the Synod of London in 1382, some as heretical and others as erroneous.

The English preacher had the courage to preach against indulgences. He sought to find answers to a nationwide crisis that affected not only England but throughout Europe and Bohemia as well: economic stagnation, plagues, and political instability.

A pope who is not a true follower of Christ is the Antichrist, Wycliffe argued

Believing that this crisis could be solved by a return of the Church to apostolic poverty, he rejected indulgences; only God, not a priest, can forgive a sinner, he said. Wycliffe stressed that the Bible was the infallible source of Christ’s teaching, the pivotal norm by which the Church, tradition, councils and popes were to be measured. Moreover, he rejected the divine origin of the papacy; a pope who is not a true follower of Christ is the Antichrist, Wycliffe argued.

Handwriting

Jan Hus knew Wycliffe’s writings because they had come to Prague University indirectly already in the 1370s. Especially after Wycliffe’s condemnation in London, the writings became popular. Hus encountered them for the first time in 1398, when he copied several of Wycliffe’s philosophical treatises in his own handwriting, adding his notes in Czech, “Hero. A hasty man. Amen, let God give so. Wycliffe, you will turn many a head. Wycliffe, God grant you eternal bliss.”

But Hus read more than only Wycliffe’s writings. There were many reform preachers in Bohemia who criticised the church and demanded its reformation. Among the most important of them was M. Matěj z Janova (pronounced as mah-TAY z εjanova), who placed the authority of the Bible above all church authorities. This became one of the main ideas of Hus for which he was later tried and eventually convicted.

From Hus’ preachings and thoughts, it becomes evident that he agreed with many of Matěj’s and Wycliffe’s ideas. But he still recognised the authority of the Church and the Pope as long as they lived in accordance with the Bible. At least until 1410, when Hus came into conflict with the papal office. Or, more precisely, with one of the three popes in office.

“Not Moses, not an earthly king, not the Pope! Their decrees are not binding unless they conform with the commandments of Christ.”

Hus sharply criticised the indulgence campaign launched by the new Pisan pope in 1410 to gain money. The preacher also openly supported student demonstrations against this practice of the Church. That was too much even for King Wenceslas. Opponents of the reforms from the ranks of the Czech and German clergy turned against Hus, who said, “Not Moses, not an earthly king, not the Pope! Their decrees are not binding unless they conform with the commandments of Christ.”

Imprisoned

Soon afterwards, Hus had to leave Prague. He spent most of his time at Kozí Hrádek (pronounced as Kozi: Hra:dek) in southern Bohemia. There he wrote what is probably his most important work, De Ecclesia, On the Church. In De Ecclesia, he summarised his views and understanding of the nature of faith. In addition, he preached outdoors, directly among people, on roads between towns and villages.

In 1414, Hus accepted an invitation to the Council of Constance. This body had to resolve the papal schism, deal with the reform of the Church, and examine heretical movements in Europe. Shortly after his arrival, he was imprisoned. In July 1415, Hus got the opportunity to speak at three hearings at which he was to renounce his opinions. But he refused, “It is better to die well than to live badly.”

Before burning him, his prosecutors put a paper crown painted with devils on his head and pushed him, saying, “We give your soul to the devil!” Hus answered, “And I commend it to the most gracious Lord, Jesus Christ.”

Legacy

It took until 1519 before someone paid attention to Hus again. That year, Martin Luther, who advocated the reform of the Church a century later in Germany, heard from Hus. This was when he found himself in comparable circumstances and was accused of preaching the heresies of Wycliffe and Hus. Luther began to study his writings and uttered the famous phrase: “We are all unwittingly Hussites.”

After the play, three Czech historians came on stage, ready to answer questions from the audience. Mostly children, who learn about Hus from the age of nine, asked, “Why did the Hussites kill and destroy churches and monasteries? What would Hus think about that? How was life back then?”

You can imagine that a play with such a story ends with a long applause. After all, Hus still comes seventh in polls for the most significant Czech figure in history. Many towns in the Republic have statues of him, the most famous in the Old Town Square in Prague. Over the country, more than 400 streets are named after him, and the day of his burning is a national holiday. For one of the most secular countries in the world, this is remarkable.

Related Articles