Hitler had 200,000 disabled people killed. “It was a vulgar massacre”

31-07-2025

Central Europe

René Zeeman, RD

An earlier exhibition called 'In memory of the children' at the Nazi Documentation Centre 'Topography of Terror' in Berlin, Germany. The exhibition recollected the 'child euthanasia' program during the Nazi period. Under this program, medical crimes were perpetrated against sick and disabled persons in Germany, including children and teenagers, based on Nazi racial ideology. More than 5,000 children and teenagers were tortured and murdered in the Nazi 'children's departments', institutions which were specially created for the purpose of extermination. Photo EPA, Maurizio Gambarini

Central Europe

Both physically and mentally disabled people were doomed to die when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. In his eyes, they were just ‘empty human shells’. “He had them killed. But to give it the appearance of normality, it was called euthanasia, gentle death.”

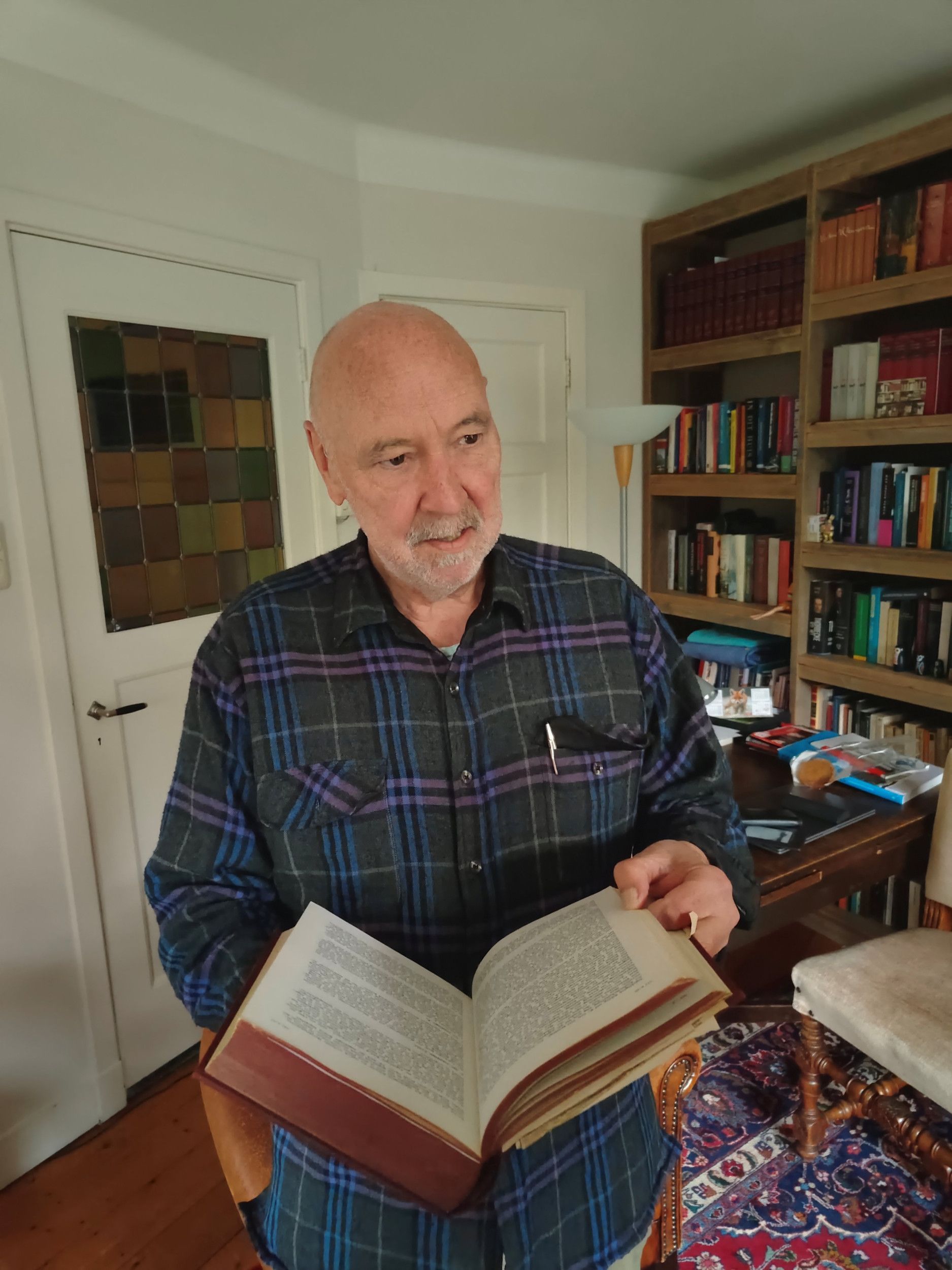

Historian Dr Dick de Mildt is an expert on Aktion T4, the euthanasia programme devised to preserve the genetic purity of the Germanic people. Hitler initiated this programme in 1939, which continued with a brief interruption in August 1941 until the end of the war in 1945. The Nazis killed no less than 200,000 mentally ill and disabled people.

De Mildt graduated cum laude in 1994 after extensive research on the perpetrators of this massacre. The academic has since retired but has, to use his own words, “stuck in the subject”.

So he read the book ‘Die Belasteten’ (‘The Burdened’) by German historian Götz Aly. The book caused a stir in 2014. Aly wrote that people more or less gave up their own family members for euthanasia and that they did not take advantage of the opportunities that existed to protect their family members.

Was that a new point of view?

“On the whole, I do not stand by the idea that parents in Germany did, in fact, hand over their children. There are numerous examples of people who were very concerned about their relative's disappearance. The organisation responsible for euthanasia transferred patients to another facility without informing the family.”

The Nazis made every effort to keep the euthanasia programme secret, but they failed. Why not?

“The killing programme was soon more or less an open secret. Residents of the six institutions where the patients were gassed noticed the smell of the cremations. Foreign journalists based in Germany also reported it. Finally, in July 1941 in Münster, Bishop Von Galen railed against it from the pulpit.”

That startled the Nazis?

“Certainly. It is always argued in the literature that Von Galen’s sermon was the reason why Hitler ordered the gassings to stop a month later. But that did not mean the end of the programme. After that, people were taken to, say, Poland and murdered there.

“In most cases, German civilians had been killed. That is one reason these criminal cases were taken up immediately after the war.”

After the war, relatives of patients who died requested the German chief public prosecutor to find out what had happened to their relatives. They knew he or she had been transferred, but after that, they had never heard from him or her again. Such an enquiry yielded nothing in most cases because the Nazis had destroyed all those files. At the same time, it illustrates that people knew about it after the war.”

Criminal cases

De Mildt adds that immediately after the war when neither the Federal Republic nor the GDR existed yet, there were some 10 to 15 criminal cases against doctors and nurses doing their deadly work in the institutions.

That is relatively soon after the war.

“Yes, and how come? The Allies said, ‘We are putting on trial the big war criminals like Göring, and, in addition, we are tackling the middle management of the Nazis.’ All German courts closed in May 1945 but were reopened within weeks because there had to be a legal system. The Allies did not give the Germans the right to try Nazi crimes, but they were allowed to deal with those against their own people. Who was euthanasia directed against? In most cases, German civilians had been killed. That is one reason these criminal cases were taken up immediately after the war.

The second reason concerns the victims’ relatives. These wanted to know where their son or daughter had gone and, in some cases, reported murder. Following that, investigations were launched.”

They didn’t dare to do that during the war?

“That happened, too. Several people filed charges because there was a suspicion of murder or wrongful death. Those people had been informed that their relative had died from, for example, the implications of appendicitis, but it had been surgically removed years before. Nothing happened to the complaints after that. They were simply ignored.”

The Nazis applied the concept of euthanasia, but it is a fact that it had already been discussed in several countries, including Germany, in the 1920s.

Did that exchange of ideas about this pave the way for the Nazis to implement euthanasia?

“In the 1920s, there was a huge debate about euthanasia, following a booklet by the jurist Karl Binding and the psychiatrist Alfred Hoche about destroying life that is not worth living. The key question was: should euthanasia be institutionalised?

The trigger was the mass deaths in psychiatric institutions during World War I. Everyone was starving because too little food entered the country due to the British blockade. Many patients in institutions perished in agony. Some psychiatrists who later practised euthanasia and were tried for it invoked the high mortality during World War I in their institutions for their motives. One even said, “The patients died like flies.”

Then you might ask, “Is that your motivation for killing those people?” Yes, because on the one hand, they considered those people “unnutze Esser”. So they ate but were of no use to society. While the healthy civilians died at the front, money was set aside for people who were of no use.

On the other hand, there was also the thought: we give them a more humane death. We don’t let them die of hunger but humanely end their lives. That didn’t happen in practice, of course, but that’s how they defended themselves.”

Alive and well

Following the publication of the booklet by Binding and Hoche, a survey was even conducted among relatives of patients. De Mildt: “To everyone’s surprise, a very large proportion of those surveyed replied, “Well, as long as you don’t tell, I’m okay with it.” What I’m trying to say: euthanasia was a topic that was alive and well.”

So it was open for discussion?

“Yes, but it was also a taboo subject. I can show that: three years before the Nazis came to power, there was a secret meeting of the ‘innere Mission’, the internal mission, of the Protestant Church in Germany to exchange views on forced sterilisation and euthanasia. That was a meeting of 25 to 30 denominational doctors from all over Germany. They debated with each other but in secret.

“Do you want to form a group of killers to carry that out? Doctors then, instead of helping people, are going to kill people.”

A recorded report reveals that they discussed the pros and cons. The historian Ernst Klee reports this in his 1989 book on the role of the German churches under Hitler. There was a doctor, Dr Carl Schneider, who literally said, “There is absolutely no scientific evidence that we can ameliorate the hereditary burden by sterilisation. There is no evidence for that. If we introduce that, we will have some kind of fashion that everyone is running after. So we should not do that.””

Does Schneider also address euthanasia?

“Yes. He said, “What do you want now? Do you want to form a group of killers to carry that out? Doctors then, instead of helping people, are going to kill people. How do you envisage that? You just can’t do that!” The same Dr Schneider completely turned around eight years later.”

What?

“Eight years later, he has become one of the top employees of the euthanasia organisation. So he made a complete u-turn. Try explaining that. Schneider was a medical doctor, a psychiatrist and originally attached to the Protestant Bethel Institute; and he played a major role in carrying out the euthanasia. Unfortunately, they have not been able to ask him why he did so, as he took his life immediately after the war. My interpretation is that he felt he could not get away with this.”

Murder

De Mildt points out that although euthanasia was discussed in the 1930s, it never came to legislation. “The justice minister under Hitler, Franz Gürtner, was very right-wing but not a Nazi. He raised the topic in a group tasked with revising German criminal law. He said of euthanasia: “We are not going to do that because that is carrying out Nietzschean thinking.” This means that euthanasia in the Third Reich simply remained murder.”

Germany was not unique in those years in terms of discussing euthanasia.

“That’s right, it happened in more countries. Nowhere, by the way, did it come to legislation. That was a bridge too far. But in the case of Nazi Germany, we do talk about a state-organised form of killing without the consent of those involved. Then you are actually talking about murder.

“To give it the appearance of normality, they called it euthanasia, but it had nothing to do with that.”

After all, why did the Nazis use euthanasia? The eugenic motive played a role, but for them, euthanasia was also a financial saving. After Hitler stopped gassing in August 1941 following protests, he had an accountant calculate how many people had been gassed. It was over 71,000. He also had an accountant calculate how much the operation would save over ten years by gassing all those patients. That is broken down to the level of the jars of jam these people ate. It is beyond belief.

It was a vulgar massacre. The Nazis borrowed the terminology. To give it the appearance of normality, they called it euthanasia, but it had nothing to do with that. Again, it was simply murder.”

Some historians argue that euthanasia paved the way for the Holocaust. Do you agree?

“In a way, that is true. When Hitler stopped the gassings in 1941, a whole group was put out of work, for example, the people who dragged the corpses to the crematoria and the like. Those people were transferred to the death camps Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor. Instead of mentally handicapped people, they were going to kill Jews. The killing in those three camps was sort of a copy of what they did in those euthanasia centres, but then at a gigantic scale.

At the same time, it was not a blueprint. They didn’t say: our euthanasia experiences are now being applied in the camps. It was just an exchange of personnel.”

So without a euthanasia programme, the Jews would have been murdered just as well?

“Absolutely. Of course, if you look at it from Hitler’s point of view, it is the step by which he crossed the threshold to mass murder.”

This article was translated by CNE.news and published by the Dutch daily Reformatorisch Dagblad on July 9, 2025

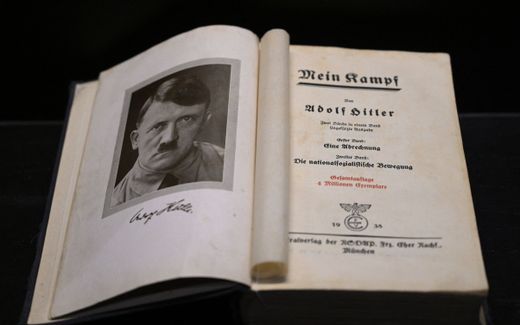

This article is the second part of a series on Mein Kampf