Is Christian nationalism a blessing or a toxic cocktail?

25-09-2025

Christian Life

Jacob Hoekman, RD

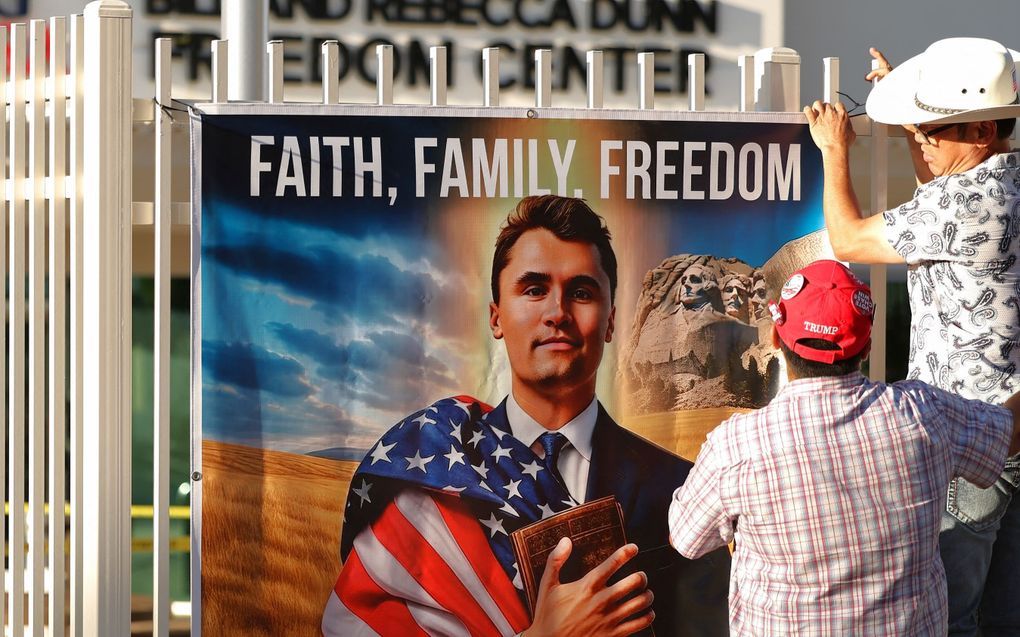

A poster of the late Charlie Kirk. Photo AFP, Charly Triballeau

Christian Life

There he stands. On an image made by a supporter with the help of AI, Charlie Kirk is surrounded by the apostles Peter, Paul, Andrew and others, who were murdered because of their faith in Christ. Placed between the martyrs for the Word of God. Is this correct?

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

It is one of thousands of images created by AI following the horrific murder of conservative Christian activist Charlie Kirk. One that stood out for me.

That Kirk’s murder is a massive scandal needs little explanation. But was he murdered for his faith in Christ, as you can hear everywhere? Based on everything we know now, the answer to that is most likely no. The shooter himself came from a Trump-voting Mormon family.

Still, it is conceivable that people see Kirk as a martyr for the faith. That is because he never made a secret of his faith; in almost every speech, he called on his listeners to give their lives to Jesus. His faith was number one for him.

The trouble is that faith was thoroughly intertwined with his political views. For instance, he defended the Second Amendment (free gun laws in the United States) as the only way to uphold God-given rights in the US – even if it means that people will be killed by shootings every year.

The same goes for his views on British colonialism (that made the world ‘decent’), the theory that white Americans are deliberately replaced by others (which he saw as accurate), Martin Luther King (a ‘terrible person’) and a long list of other views going around in right-wing America and especially in the circles around President Trump. Those views cannot be called Christian, but what was Christian and political were intertwined in Charlie Kirk’s case.

In this, Kirk showed himself to be a typical Christian nationalist. That is someone who connects his country’s national identity with the Christian faith, and expects the nation to defend Christian culture and values.

Now, the big question is: is there anything wrong with that? And if so, what exactly? Standing up for Christian values in our society, for instance, is that not also what many Christian political parties have in mind?

To start with the latter: yes, that is right. In the Dutch context, it was one of the significant differences between the founding father of the Dutch Reformed SGP party, G.H. Kersten, and Abraham Kuyper, the founder of the ARP party, in the early 20th century. The latter believed that church and state should be strictly separated. Kuyper did not want a Christian, but a free state where the Christian faith could thrive without imposing it on others. If, on the other hand, you have a people’s church, the next step is all too soon the stake, where wrongdoers get killed, Kuyper argued.

Of course, this remains to be seen. Still, the fact is that Christian nationalism paves the way for one particular political interpretation that then represents the Christian view. That is what is now happening in abundance in the United States. A Christian is conservative, supports Trump, has strong objections to protest movements such as Black Lives Matter and has little use for progressive climate policies.

The more people feel this way, the greater the social pressure becomes to conform to this, including in the church.

For Kirk, this was deliberate policy. He was known as an advocate of the Mandate of the Seven Mountains. Supporters of this want to ensure that as many like-minded people as possible are appointed to positions of influence. The mountains refer to seven important societal domains: government, church, family, education, economy, media and art. In all these domains, the same sound of Christian nationalism should resonate.

The problem with this is that only one correct, Biblical way of thinking emerges – while, of course, all sorts of other positions are possible. Any particular political theory can never capture Christian faith in all its comprehensiveness, be it progressive left, conservative-nationalist right or something else entirely.

But it could be worse. At its worst, Christian nationalism can take on traits that go directly against the Bible. “Jesus said the greatest commandment was to love. Kirk preached that empathy is weakness and that firearms deaths are the price of freedom,” an American pastor concluded.

Others point out that Christian nationalists often consciously or unconsciously equate their country with Old Testament Israel, which has a unique and chosen position. But from Christ’s teaching on the Kingdom of heaven, such an equation is theologically indefensible.

So, one should be very wary of marrying Christian faith with nationalistic policy programmes. Most of the time, nationalists have a wishful thinking about cultural dominance, political power and protecting their own “kind”. These may still be defensible secular political goals, but at least they are not the message of the Sermon on the Mount.

What is the alternative? If it were up to Abraham Kuyper, the alternative would be freedom for every religion. But in doing so, you can end up undermining that freedom, for instance, by allowing currents that ultimately want to abolish it.

Another option is that of a kind of cultural Christianity, something the scholar Paul D. Miller, respected in Republican circles, argues for in his book The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism. But there are snags in that, too.

Taking these alternatives further requires a separate narrative. It is certainly not the case that perfect alternatives to Christian nationalism are available. But one thing is clear: at least those alternatives do not measure up to an elective status, as if the nation were the new Israel. And that danger does lurk in various forms of Christian nationalism.

This article was translated by CNE and published earlier in Reformatorisch Dagblad on 20 September 2025.

Related Articles