French ethics committee passes euthanasia proposal

Activists of the Association for the Right to Die in Dignity (ADMD) protest in support of euthanasia in Paris. Photo AFP, Kenzo Tribouillard

Western Europe

The National Consultative Ethics Committee (CCNE) thinks it is possible to allow self-determined dying ethically. On Tuesday, it ruled that there is “an ethical application of active assistance in dying” under strict conditions. The ruling means that the French government can go ahead with the drafting of new legislation concerning the end of life.

The CCNE writes in its report on the issue that it sees no objections against the legalisation of a chosen death. That is reported by La Croix.

One of the rapporteurs of the CCNE, Régis Aubry, who is also a doctor in palliative care, says that this is only possible under strict conditions that limit the process. In the words of the committee: “the possibility of legal access to assisted suicide should be open to adults suffering from serious and incurable illnesses, causing refractory physical or psychological suffering, whose vital prognosis is committed in the medium term.”

Currently, the French law on self-determined dying specifies that it only applies to people who are expected to pass away in the short term: in a few days or hours. By broadening the concept of self-determined death to the medium term, people with cancer, who are expected to die within several weeks or months, can choose to commit suicide as well.

Other ethical benchmarks should prevent the abuse of the possibility of self-determined death, the committee emphasises. In the case of legalisation of active assistance in dying, the request can only be honoured if it is expressed by “a person with decision-making autonomy at the time of the request, in a free, informed and repeated manner, analysed within the framework of a collegial procedure.” Furthermore, physicians should be able to refuse the procedure, benefitting from a conscience clause.

In addition, more attention should be paid to palliative care so that people have more options to be taken care of at home. If palliative care is improved, people may see more possibilities for their life than to step out of it.

The ruling of the CCNE is historical because it breaks with the decisions of previous ethics commissions, which had, up till now, always opposed active assistance in dying.

According to the CCNE, there are two ways of organising assistance in dying. The first one is euthanasia, where a doctor performs a lethal procedure. The second is assisted suicide, in which a person can end his or her life him or herself with medically prescribed drugs. The CCNE recommends the second way.

Debate table

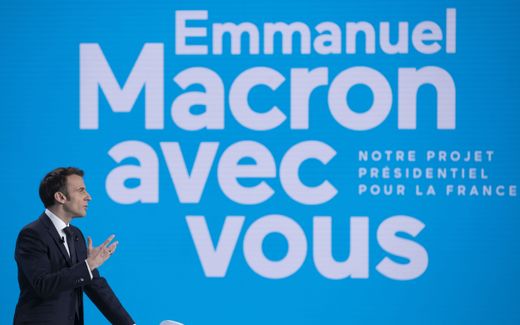

It is no surprise that the euthanasia debate is sparked again. President Emmanuel Macron and the French health minister Brigitte Bourguignon are known for their pro-euthanasia stances. Macron wants to adopt a law on the end of life in 2023 at the latest, La Croix reports. Whereas he kept euthanasia from the debate table during his first term, he put the issue on the agenda again as he is currently serving his second term.

Is the current law sufficient?

Another reason why the CCNE looked at the euthanasia idea again is that some people in France are not satisfied with the current legislation on the end of life, La Croix writes. At the moment, a patient can request limitation or cessation of his treatments or deep and continuous sedation until death.

Anne Vivien, vice-president of the Association for the right to die with dignity (ADMD), argues that too many scenarios are not currently covered. “The sedation can only be applied if the prognosis is life-threatening in the short term. But what about situations where the disease is incurable but does not lead to death in the short term?” She says that the short-term criterion that is currently in place prohibits the shortening of long-term suffering. If it were up to Anne Vivien, the focus of the current law – for patients who are going to die – should shift to patients who want to die.

On the other hand, Ségolène Perruchio, a doctor in a palliative care unit and vice-president of the French Society for Support and Palliative Care, argues that the current law is sufficient. She says that the law covers all illnesses and that palliative care should be so good that it relieves symptoms so that people do not suffer unbearably. “We accompany, we readapt the treatment, we invent. It is our job.”

She argues that the current law is self-sufficient because people usually do not choose self-determined dying until palliative care cannot do much more to relieve their suffering.

If self-determined death were legalised, society and the government would have to make a choice, Perruchio says. “Should medicine meet all demands? And where do you stop? Is euthanasia first authorised for physical pain, then for psychological suffering? For the impediments of old age such as deafness, blindness, if they are deemed disabling?”

Related Articles