Reading on the narrow way

16-09-2022

Christian Life

Rudy Ligtenberg, RD

Photo Unsplash, Michał Parzuchowski

Christian Life

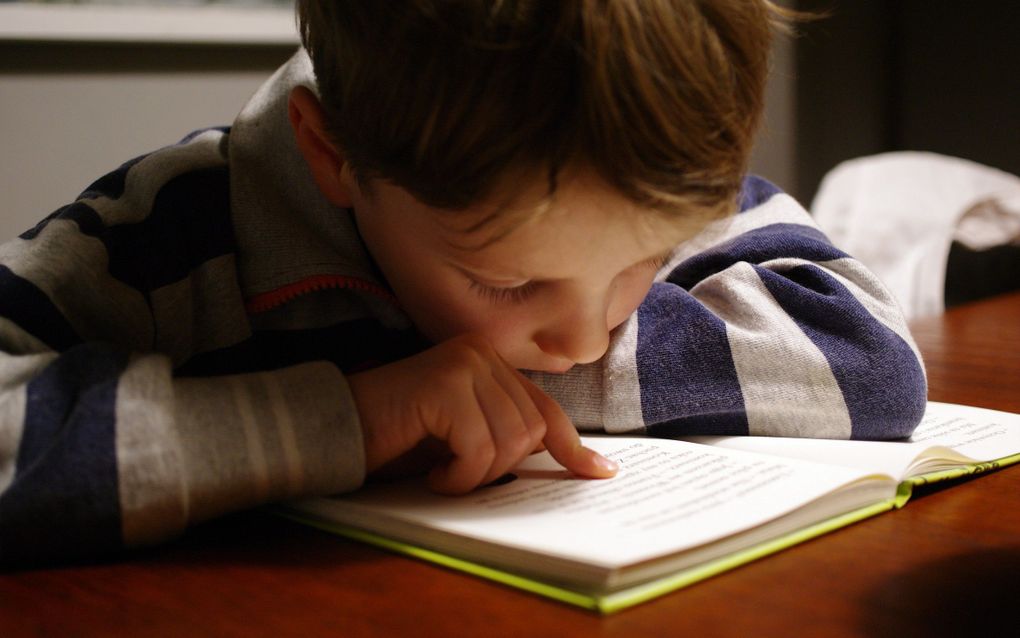

What happened to the days when mothers would chase their children outside because they were too captured by a book? By now, many parents and teachers have reached the point where they are happy that youngsters are reading – even if it is just a comic book.

The decline in reading is considered one of the more significant concerns of our time. No less than "the viability of a democratic society" is at stake. That is what Prof. Adriaan van der Weel and reading expert Ruud Hisgen write in their study "The Reading Man", published last spring.

Conversely, reading is good for society, according to the 2019 report "The impact of the book" commissioned by KVB Boekwerk, a knowledge and innovation platform for the book sector. Readers have a more positive self-image and are more skilled workers; they have fewer prejudices and care more about others. Moreover, the book trade provides the added value of around a quarter of a billion euros, at least to the Dutch economy, according to the report.

For Christians, there is another crucial aspect. Books are indispensable to the life of faith. After all, the Bible itself is a collection of books (Biblia). For this reason alone, reading skills are vital.

Take and read

However, all sorts of other valuable books have appeared over the centuries that shed light on the human deficit and the grace-filled message of the Bible.

Take the "Confessions" of the church father Saint Augustine (354-430). There, he candidly recounts his sinful early years and the radical conversion that followed. Hearing a child's voice singing "Tolle lege" (take and read) in Milan prompted him to start reading Saint Paul's letters. He had a breakthrough in his faith.

Or take the Reformer Calvin's "Institutes", in which he puts the Christian doctrine of faith into crystal clear words.

Or take "The Pilgrim’s Progress" by John Bunyan, an evocative story of Christian fleeing the city of Destruction to find a safe refuge at Mount Zion.

Or take...

Those books shape us, immerse us in the age-old Christian tradition and help us find footing in a time when everything is shifting, and certainties are challenged. Especially now, we need to be (re)shaped in our views. Often, we find ourselves in a digital bubble in which we are only confirmed in our opinions; or we are carried along willy-nilly by all kinds of dubious ideas that are given a semblance of truth by the power of social media.

Ancient house

The Gouda history philosopher Dr Ewald Mackay realised this better than anyone else. In 2016, he published "A Reading Room in the Big House" (Een leeskamer in het grote huis). That is a guide to reading texts from twenty centuries of Christian faith tradition. Mackay describes this tradition as an ancient house within which the treasure of faith is kept. To live in this house, it is essential to take note of the sources bequeathed to us.

There, he writes:

The voice of the Church is not a voice from a romantic paradise. My dwelling in her reading room is not an escape from harsh reality. The Church's voice resonates precisely amid the raging of the whole world. Her voice is often the voice of martyrs during struggle, difficulty and pain. But it is also a voice that invites us into the inner room. When the day is over, and we have left the bustle of the world behind, we may dwell for a while in the oasis of the inner room. We may come into the garden of which the Song of Songs speaks: the enclosed garden of love, where the bride may sometimes meet her Bridegroom. Our souls then blossom and grow again. Then we may experience something of the joy God gives us. The experience of joy often only lasts for a short time. After all, we are not meant to want to stay on earth forever. But we may always dwell for a while in this quiet blooming garden of God. In my mind's eye, I see the reading room before me: it adjoins an enclosed courtyard garden, so to speak.

That does indicate the importance of reading. But how does it become attractive for young people to pick up a book again? Apart from parents, an important task lies with education. The problem, however, is that in secondary school, reading enjoyment decreases drastically in many cases. The compulsory reading list and the focus on technical reading are to blame.

Formidable competition

Moreover, with the rise of the internet, reading more extended texts faced formidable competition. Social media, games, TikTok and movies have become tempting substitutes for the book. In these hectic times, finding the peace and quiet needed to read a book is almost impossible.

Here lies a dilemma for Christian parents: after all, not every book is responsible, especially in the literary field, there is a lot of chaff among the wheat. In orthodox Christian circles, reading has traditionally been held in high regard, but not unreservedly.

"Good" (i.e. edifying) books are praised, but it was often different in the case of novels and other idle readings. A heavenly-oriented life did not match with a useless pastime – time is a time of grace, after all. The word of Ecclesiastes (chapter 12) was quite often invoked: "And what is above these, my son, be warned: of many books to make is no end, and much reading is fatigue of the flesh." Isaac da Costa's (1823) critique of the "heart and mind ruining and disenchanting novels" echoed long after in this part of the Reformed community, which pursues piety and worldliness and, with the 17th century Dutch preacher Lodenstein, professes and lives the "down here it is not".

Confrontation

However, throughout the centuries, there has been a current in Christianity with a more open attitude towards culture, of people who make serious efforts to learn about their own time and who, in their education, look for forms to confront the outside world with Biblical principles. They see a shining example in the apostle Paul, who at the Areopagus, with knowledge of pagan literature, created space for the proclamation of the Gospel.

Undeniably, the latter movement has become more dominant in the pietistic Reformed circles in recent decades. The arrival of Reformed secondary schools, institutions and a newspaper accelerated the emancipation of the Dutch pietists.

The level of education increased, studying at college and university became commonplace, important social positions came within reach, and prosperity rose. The SGP, the party of the conservative Christians, entered the political arena more confidently and increasingly and, with electoral success, linked Biblical witness with practical action. Tellingly, since last spring's municipal elections, over 80 per cent of all SGP councillors have been in coalitions of parties supplying aldermen. Far more than any other party, research by the secular Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad showed. The political Calvinists are also making themselves heard much more often in places that were previously taboo, for example, on television talk shows.

One could say that conservative Christians have become more attentive to functioning in this life. The question of how to live as a Christian has become more relevant, while the notion of being a stranger is taking a back seat. This also changes the view of leisure.

The notion that every moment of the day is a time of grace and should be spent meaningfully (that is, with a view to eternity and personal soul salvation) has given way to the idea that there may also be room for relaxation, amusement and idleness. Holidays, sports, gaming, film, culture and going out have become less controversial in pietistic circles – at least among the younger generations. The increasing focus on a healthy lifestyle (sometimes to the extreme) also fits into this development.

Stimuli

In a digitising world, the number of stimuli is increasing. The smartphone dictates life, attracting attention often with notifications, beeps and bleeps. In the boom of information, it is challenging to seek depth. "What digitalisation most undermines are mental discipline, concentration, the ability to think and reason abstractly, and to understand arguments," write Van der Weel and Hisgen in "De lezende mens" ("The Reading Human"). Besides, why read a newspaper when websites summarise the news practically for you? And why read a book when there is also an engaging Netflix series to watch?

The immediate satisfaction of needs, hopping from hype to hype and focusing on images characterise the lives of many modern people, Christians included. It has infiltrated society so much that it is difficult to break free from it. Yra van Dijk illustrated this beautifully in NRC Handelsblad earlier this year with her review of "De lezende mens":

Digitisation is to the reading crisis what fossil fuel is to the climate issue. We can no longer live without it, but computers and smartphones are "disastrous" for the attention span that reading and writing require. While I was typing these first 471 words on my laptop, I have already read four apps on it (about Friday's Book Ball), visited websites ("who is Ruud Hisgen actually?") and had a quick look to see if it will rain this afternoon because otherwise, I would first take the dog out for a walk.

Reading behaviour in pietistic circles reflects developments in society. Interest in classical theological works –such as the Augustine’s "Confessions", Calvin's "Institutes", and "The Christian's Reasonable Service" by Brakel– has been declining for years. They are too thick, too difficult, and not of our time.

Who still recognises himself in the image of Rev Kersten, who, as a boy of 12, 13, read Mr Justus Vermeer's catechism explanation with his feet in cold water? What is still read in this field has often been retranslated and abridged to still bring the content to the attention of new generations – sometimes indeed successfully.

Shifting

But there are also shifts in content regarding what is read in the theological field. Dogmatic works give way to popular theological books, stories of experience, diaries and books on practical and ethical topics, often also of Anglo-Saxon origin. In short, books that help to shape Christianity in today's society and are strongly focused on the here and now.

That is another critical shift that has been going on for some time, Reformatorisch Dagblad journalist Enny de Bruijn asserted in June in her Mr H. Bos lecture, which she delivered at the invitation of the HDC Centre for Religious History. During the 20th century, edifying books gave way to the novel among many readers. "That is THE major development in Protestant reading culture, a development that began as early as the 19th century and continues to this day." Here too, attention is shifting more and more to the world around us, according to De Bruijn.

Changed image of God and man

The image of God and man have changed dramatically. In most novels, there is no longer a judgmental God who punishes people's sins, and with whom you as a human being must therefore come to terms through grace. The theme of conversion has been pushed into the background. Instead, the stories are mainly about the complexity of relationships, where people have to learn to live with themselves and others in a good way.

This shift has undeniable implications for the life of faith, human and God images, and the view of life here on earth and of what comes after this life. After all, books always do something to the reader, especially if they are well written. The moral of the story slips in unnoticed. For instance, in Swedish crime author Stieg Larsson's immensely popular Millennium trilogy, the sympathetic protagonist Blomkvist has a casual relationship with a married woman with the consent of all concerned. Simply as if it were the most normal thing in the world.

Key

Yet the key to tackling the reading problem lies with novels and literature. Good education starts with reading fiction, Ewout van der Knaap, professor of German-language literature and culture at Utrecht University, argued earlier in NRC Handelsblad. "Reading fiction increases reading performance. Literary books of all levels therefore help. To expand your vocabulary, it is better to read literary prose than other texts." Reinforcement of literary reading is necessary, he says. "Reading, didactics and study choice are interrelated," he says. This alone should encourage more work on good Christian literature; edifying prose is sufficiently available.

Of fundamental importance here is fuelling the pleasure of reading. Van der Weel and Hisgen, in "De lezende mens", talk about absorbed reading. In this form, the reader is wholly carried away by a book, often a novel or thriller; he does not approach the text critically but immerses himself in it, like in a warm, relaxing bath. For a moment, he is in another world. Reading pleasure is paramount, but an additional effect is that reading literature greatly enhances language skills.

In-depth reading needs reading pleasure

Reading pleasure and language skills are needed to transition to in-depth reading. That is a way of reading in which the reader reads a text with attention and concentration, thinks about it and makes connections with other texts, with other thoughts and with his own life. He questions the text with critical distance. In this way, he is shaped and forms his own views.

That requires lifelong training, warn Van der Weel and Hisgen. They compare in-depth reading to top-class sports. But readers get a lot in return, especially if they manage to unearth treasures from the Christian tradition. In a turbulent time, full of volatile rumours and fake news, these provide counterpoint and footing. And ultimately, they lead to a better understanding of Scripture.

Proven resources can also prove their worth in our time. If only we are willing to invest in them, silence the smartphone a bit more often, make room in the diary – and just start reading, for example, in "A reading room in the big house" by Ewald Mackay.

The impact of reading books

Reading encourages thought, more so than, say, watching a film or gaming.

The reader's imagination is enhanced. As a result, people develop more understanding of others and hold on less to prejudices

When people get absorbed in a story, they develop empathy. They learn to better empathise with the other person's experience. Empathy has a positive effect on self-image

Digitalisation and globalisation require different skills. New jobs require empathy, creativity, leadership, critical thinking and thinking in scenarios. Skills you acquire or strengthen with reading

Readers are more than 25 per cent more likely to be healthy than non-readers. That is because reading and processing information contributes to how a person gets by in society

Reading leads to happiness: it offers positive experiences. Relaxation, coping well with emotions, higher emotional intelligence, and a positive self-image contribute to personal well-being

From: “De impact van het boek” (The impact of the book), KVB Boekwerk, 2019

This article was translated by CNE.news and published by the Reformatorisch Dagblad in a special glossy on September 9

Related Articles