Digital Bible readers read more – but understand less

27-10-2023

Christian Life

Prof. Joel Halldorf

Paper or screen? The message is the same; the experience is different. Photo Digital Bible; Techbuild Africa

Christian Life

The best Bible is the one we actually open and read. But is that a paper version or a digital Bible? Research shows that reading on paper has a deeper impact, writes the Swedish theologian Joel Halldorf.

Reading is under debate in all Western countries. Teachers sound the alarm and warn that the children’s reading ability is declining. In my home country, Sweden, the cultural editors of the six largest newspapers wrote a joint appeal for more printed books, libraries, and reading in the schools. In Great Britain, the National Literary Trust warns that more than half of the people in the country say they don’t enjoy reading in their spare time.

Bookshelf

We read less and less; that is what we see and know. But there is one book we stopped reading before we abandoned the others: the Bible. Last year, the American Bible Society reported that 26 million Americans stopped reading in 2022 alone.

In other countries, the decline has been slow but steady. In 1949, 16 per cent of Swedes read the Bible regularly, but by 1970, the figure had dropped to 10 per cent. In 2016, a survey showed that 7 per cent read monthly and only 2 per cent read daily.

Most people own a Bible, but it sits unread on the bookshelf. This decline in reading has also been noticed within the churches, and many address the problem with the hope of increasing Bible reading among Christians.

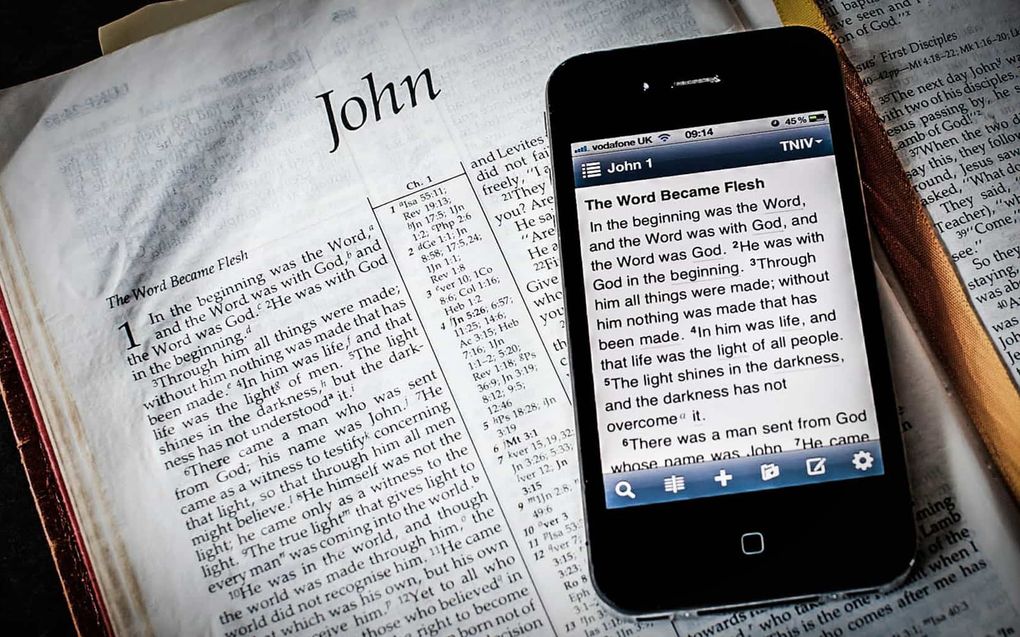

But how will that goal be accomplished? Much hope has been placed in the digitisation of the Bible and the countless apps designed to support Bible reading. In sheer numbers, these have been hugely successful. The most popular, YouVersion, has been downloaded to half a billion phones, iPads, and computers.

Push

The technology has several advantages: If you have the Bible on your mobile, it’s always in your pocket so that you can read it anywhere. It is also possible to set it so you get a “push” that reminds you to read. Further, one can easily subscribe to Bible reading plans and get some edifying verses on the screen daily.

Such advantages are one reason evangelicals in the United States have been working hard to develop digital Bibles. Platforms like Quickverse, Logos, Bible Gateway and YouVersion all have ties to this branch of Christianity. Evangelicals are often technology optimists, and they have a strong faith in the positive effects of Bible reading. It is only natural that they would try and use technology to boost religious reading.

Confusing

But what is it really like to read the Bible on a screen? In the recently published People of the Screen (Oxford University Press), theologian and tech developer John Dyer examines this. In the study, he divides congregants from three churches into two groups. He lets one read on a screen and the other in a regular paper Bible.

The result is interesting, to say the least. The most significant advantage of digital Bible reading is that it is easier. Those who follow a mobile Bible reading plan read more often than those who use printed Bibles.

The problems appear when it comes to understanding. Countless studies show that we understand less when we read on screen, which also applies to Bible reading. Dyer let the people in his research read the letter of Jude (a book that few have good prior knowledge of) and then tests what they remember. It turns out that those who read the text in digital format remember less than those who read it in print.

But the most significant difference arises when they describe how they have experienced the reading. Twice as many digital readers state that they find the text confusing.

When interviewed, many screen readers admit they read carelessly. It seems difficult to approach the text on the phone with a sense of devotion: “It felt more like skimming an email to get it done than really studying God’s word,” says one.

Dyer’s study lands in this paradox: Digital readers read more but understand less.

As noted above, evangelicals tend to be optimistic about technology, and the study’s participants are no exception. Before they started, 64 per cent were confident that digital technology could deepen their spiritual life. In fact, no one (zero per cent) was sceptical. But the experience fostered reflection. After they tried digital Bible reading, the optimism dropped dramatically: Only 27 per cent were positive, while the percentage of negatives increased from 0 to 25 per cent.

Relationship

Sometimes, it is said that the best Bible is the one we actually read, and indeed, there is some truth in that. At the same time, it is clear that if we do get around to reading it, the traditional printed Bible is superior to the digital version. One reason for this is that it is persistent. While the digital text appears and disappears every time we open it, the printed book is always the same. This allows us to develop a relationship with it: Not only to the Bible as a text but with our own physical copy.

The widespread habit of reading with pen in hand is an expression of this relationship. This is particularly common among evangelicals. It is an interesting practice: While the Bible is regarded as God’s exalted word, each believer’s Bible receives a personal touch through underlining and annotations. If we mark a verse that comforts us in a crisis, it remains a constant reminder of how God has walked by our side.

When we read with pen in hand, reading becomes a dialogue. This habit goes back centuries: in the 18th century, devout readers would make notations of important spiritual events in their own lives – the date for their conversion, for example.

This turned the Bible into a book that did not end with the last page. Through notes and annotations, the story continues as the Holy Scripture is intertwined with the reader’s personal life. They write themselves into the story about how God acts in the world, and the sacred story continues in their own lives.

Joel Halldorf is a professor of church history at the University College Stockholm. His latest book is Bokens Folk, a study of books and reading from Jesus to Donald Trump. An earlier version of this article was published in the Swedish newspaper Dagen.

Related Articles