Francis Schaeffer was an apologist, but not of the middle-class Christianity

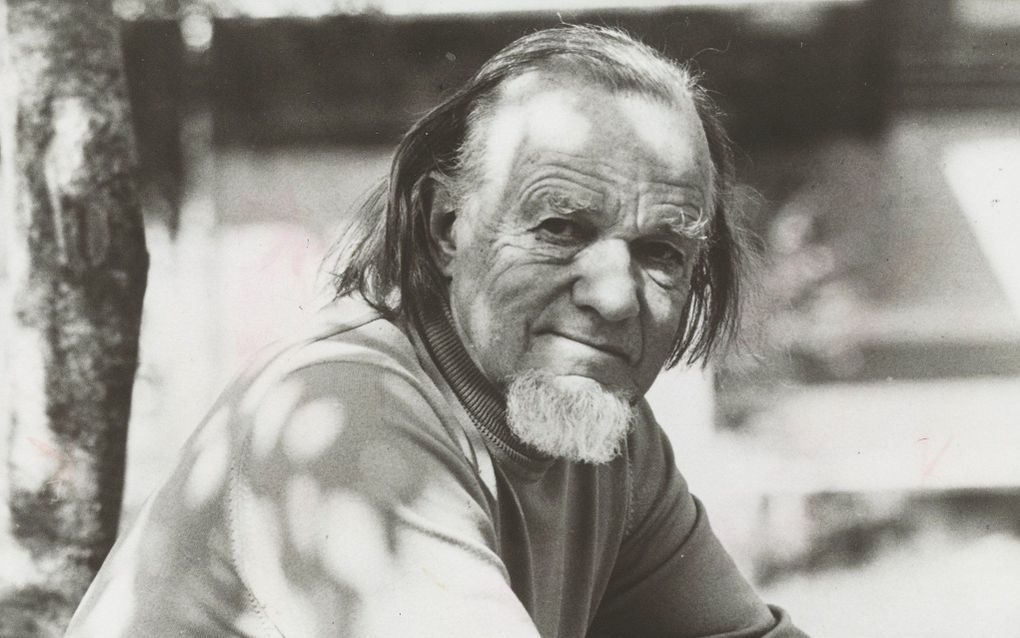

Dr. Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984). Photo RD

Christian Life

Francis Schaeffer looked like the hippies he debated with. But that was style, not content, says an expert forty years after his death. Schaeffer said that everybody had a belief, even an atheist.

Receive CNE's weekly newsletter? Feel free to sign up here.

If God does not exist, everything is permitted, Dostoevsky wrote. However, Western citizens still love law and order. Schaeffer saw this as irrational and loved to unmask it. First and foremost, he was an apologist of the Christian faith.

Not many Christians felt that the postmodern era was coming. But Schaeffer (1912-1984) showed in his well-known books as The God Who Is There and Escape from Reason that he sensed the change. Rationality was going over in irrationality, he thought.

One of the people who learned much from Schaeffer is Stefan Gustavsson, director of Apologia in Sweden. His centre just published a new trilogy of Schaeffer’s books The God Who Is There, Escape from Reason, He Is There, and He Is Not Silent. “I am happy to say we have newly translated those books in fresh Swedish.”

Gustavsson thinks that there is still interest in Schaeffer’s work in Sweden. People of his generation –just above 60– might be influenced by his work in the past. “In the 60s and 70s, Schaeffer had quite a new perspective for us. He was an intellectual. We were not used to that.”

The evangelical tradition in Sweden is not intellectual but stresses the spiritual aspect. “But in the most secular country that is often hostile to the Christian faith, this robust voice from Schaeffer was very much welcome. Many people of my age have profited from him, directly or indirectly.”

Together with C. S. Lewis, Schaeffer was the most important apologist of the 20th century, Gustavsson thinks. “Lewis was a man from the academic world, coming from the two most prestigious universities in the world, Oxford and Cambridge. Schaeffer had no organisation or platform. He worked as an American missionary from a chalet in Switzerland called L’Abri. But that had such an impact on students that later became Christian leaders.”

One interesting aspect of Schaeffer’s work is his attention to art and music. Why was that?

“For him, God was not solely the source of truth but also from beauty. In this, he was kind of unique.

He could value an artwork’s beauty but criticise its ideas. He believed that the artist’s worldview was always reflected in his work. He saw that much art had the message that there is no dignity and no hope.

He was a friend of Hans Rookmaaker, a professor of art history at the Free University in Amsterdam. Through this, he always had good access to the proper sources in the world of art.”

After his death, we have moved on forty years. What does he still have to say?

“Some of his illustrations might be outdated. But his central perspective is still relevant.

For me, this is his strong emphasis on truth. At the moment, we see that many deny objective truth. I believe Christ has risen, but the man next door does not. Schaeffer claims that the truth of God is independent of you and me. Christ has risen or not, whether we accept that or not. Much of his work is about this.

The other point is that Western culture is moving away from its Judeo-Christian roots. In other words, our universe is seen as all there is. Schaeffer says that the logical consequence of this is that there is no meaning any longer, no beauty, no hope. But the strange thing is that not many people come to that conclusion. For Schaeffer, this is irrational, as he shows in Escape from Reason.”

Whether Schaeffer calls this irrational or not, most Westerners have learned to deal with this, haven’t they?

“Indeed, not many people feel this tension. But look at Yuval Harari’s bestseller Sapiens. There, you read that all talk about dignity is without foundation. So, the only thing we can survive with is tolerance.

Currently, 30 per cent of young men in Sweden don’t see meaning in life. This is the case in many Western countries. Psychological problems are on the increase. Why is this? I think because our culture cannot give meaning if biology is the only thing there is.”

In “The God who is there”, Schaeffer puts forward the antithesis as central in the Christian worldview. What did he mean by that?

“The antithesis means that if something is true, the opposite cannot be true. So, for me, there is a God, but for somebody, probably not. Schaeffer saw that the synthesis tries to combine the opposite options, although they cannot be true simultaneously.

For a doctor, such an approach would be unthinkable. If a patient is sick, he deserves to know the depressing diagnosis. You have to relate to this truth. For Schaeffer, it was the same in religious matters.”

Well, how are we going to convince people in our postmodern era?

“Of course, we are in favour of tolerance. It is not the state that can force us to believe or not.

On the other hand, tolerance cannot mean the truth does not matter. It would help if you had confidence that, in the long term, the truth will speak for itself. Tolerance cannot mean the truth is hidden and cannot be trusted.

The crucial thing I learned from Schaeffer here is that everyone is a believer. No presupposition can be proven. Most people do not accept this and only see religious people as believers. But as Christians, we have to challenge this.”

In a conversation with another Christian, Schaeffer once said: We have the better system. To which the other replied: No, we have the better Person. How about this: was Schaeffer only defending a system?

“No, he wasn’t. Although his philosophical writing sometimes gives that impression. But people who visited him in L’Abri experienced his spiritual side, for instance, when praying together. You can also see that in his book True Spirituality.

Schaeffer was convinced that many people did not come to the faith as the prison guard in Philippi from Acts 16. He said, what must I do to be saved? Schaeffer would have answered the same as Paul: Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved. However, most people come up with other questions, some of which are intellectual obstacles. And you have to solve that first.”

In “The Great Evangelical Disaster”, Schaeffer complains about Christians who go for “accommodation”. What does he mean by that?

“He saw that many evangelicals tried to communicate as much with the secular culture and to do away with Biblical truth. He saw that as giving in to the liberal theology, which no longer believed in walking on water and other miracles in the Bible.

Schaeffer was not unaware of hermeneutics. He also wrote that Genesis 1 could have several interpretations. But he was convinced that confidence in the Bible should not be diminished.

Looking back, I think this was a prophetic insight. Today, many evangelical churches have changed their position regarding everything related to LGBT. However, the Bible is obvious in this. Another issue is the ultimate judgment. There is a universalist tendency in which no one can get lost. But that is difficult to relate to Jesus’s teaching.”

In “The God Who is There,” he also speaks about the problem of most churches consisting of middle-class people. Do you recognise that?

“Oh, yes. The Pentecostal movement in Sweden started to attract working-class people. But because of the church’s teaching, school education and orderly family life, the people grew up to a middle-class level.

On the one hand, this is a blessing. But on the other hand, it is possible that people only come to church for personal peace and affluence.

Of course, Francis and Edith Schaeffer lived very differently. In their first congregation, they had many people from the shipyards. Later, in L’Abri, they welcomed all sorts of people to their home and formed a community. And he opened himself to the hippies, too. So, this was not a middle-class project at all.”

Related Articles