Jesus could read but very slowly; scanning did not yet exist

Halldorf writing at his desk. Photo Zandra Erikshed

Christian Life

A child needs less than a year to learn to read. But it took centuries for mankind to develop the reading technique. Would it be something that we could unlearn as well?

Prof. Joel Halldorf can not only read; he also writes about it. During a drive in Sweden, he tells how generations of monks and churchgoers gradually refined the art of reading. Last year, he published a book about this in Swedish: "Bokens folk"; people of the book.

Halldorf is theologian and lectures church history at the Enskilda Högskolan in Stockholm (EHS).

We are speaking by telephone now while you are driving in Sweden. Would this conversation have been possible without the art of reading?

“No. Cultures in which reading does not exist do not progress in the same way. Reading and writing make the difference between history and prehistory.”

How would the world have looked like without reading?

“Well, reading is the foundation of many things we see in our time. There would be no school or university. Neither would there be a democracy. And it is difficult to think about a church or a monastery without books.

Reading helps us memorise information, which aids progress. A book is not just a container of information but also a tool that can help us reflect, meditate, and even pray.

In the history of the church, books were often used as a means of meditation. In the monasteries, the monks read as a way of prayer. Something similar can be seen in the edifying reading of the revival movements.

Nowadays, we mostly read to find information – not so much as a way to reflect or pray. As a result, knowledge is expanding while wisdom is shrinking. The speed with which we produce new texts even threatens reflection. Skimming is the new reading. The loss of slow and reflective reading is at the heart of our modern crisis.”

The first chapter of your book asks: Could Jesus read? What is your answer?

“I think, yes, He could. Some scholars believe He could not, given His class background as a simple carpenter. But He would never have been acknowledged as a rabbi if He could not have read. What is true, though, is that we need to consider that an oral culture shaped Jesus. This influences how he expresses himself and makes Him excellent in debates.

For me, it is still an open question whether He could write. The only account of this we have from John 8, where Jesus writes in the sand.”

If He could read, what would His reading technique have been?

“He would read aloud, like everyone in His time. Reading was something you did in a group. Reading aloud is a good way to read slowly, repeat a verse, and memorise. The fruit is that you learn the Psalms and other sacred texts by heart. That was the goal of the schools connected to the synagogues.

On the cross, we hear Jesus quoting from Psalm 22. His memory was a treasure from which he could pull a text that speaks about Himself. He did that all His life, but even as a comfort at the very end.”

What has the role of reading been in the history of the Christian faith?

“From the first days, reading has been central. Congregations very much looked like study groups. Together, they read the letters of Paul, the Gospels, and the Old Testament.

Christians used codices instead of scrolls. Codices looked like our books today and were easier to use. As the Jewish identity is based on the Torah and the temple, the Christian identity is based on Bible reading and liturgy.

Until the 18th century, most reading was done in a group. Personal reading on a wide scale was not known until the 1700s.”

Why was that?

“First, books became cheaper through the printing press. Before that, personal reading was only accessible to rich people or monks with access to the library. Books and pamphlets became available for the masses through the printing press and later the steam press. That influenced the Reformation and, later, the revival movements in Europe. In the social realm, the worker’s movements would not have been possible without printing.

But even before the invention of the press, there was something else: the introduction of the space between the words around the year 1000. Before the year 1000, all words were connected to each other, and texts were written in scriptio continua. This means that you had to read aloud to hear what was written. But by separating the words, the new technique of silent reading came within reach. Now, it became possible to read the words with your eyes only.

Augustine tells in one of his writings that he once saw Ambrose reading without moving his lips. He could not understand what was going on. Silent reading was only possible for a few people with a unique talent for that.”

Augustine’s “City of God” is still too thick for many. But if you would have to read that aloud, it would take ages to finish.

"Yes, but people read that book with a different expectation. They did not start a book to finish it. We read for information. But historically, the main goal of reading was the transformation of the heart. Important was that it made an imprint on your soul. In the Antiquity and Medieval times, the readers were not in a hurry and had time to read, digest, and read again. That is ruminating reading. Books were tools for meditation.”

Luther and Calvin show that they were very well-read. What reading technique did they use?”

“I assume they have read for themselves and silently. The humanistic movement shaped Luther. As a university professor, he had to cover many texts and compare them together.”

The Scandinavian countries where you are from are known for their pietistic revivals in the 18th and 19th centuries. What role did reading have there?

“In my country, Sweden, the pietists were called the readers. That is how they are labelled in church protocols and newspapers. That says enough. The Pietists read the Bible once or twice a day.

They also read books for edification in groups. Repeating and digesting the text shaped the heart and transformed the reader. By doing this, the Pietists did the same as was done through the ages of Christianity from the early church onwards.

However, in the revivals, they also discussed the texts in groups to form their own judgment. They did not follow the priest but their own conscience. This was in the spirit of the Enlightenment. The philosophers shaped the Enlightenment for the elite; the pietists represented the people’s Enlightenment. This was very important in shaping the democratic culture in Western countries.”

Halldorf thinks the revival movements created strong communities because of their reading culture. “I find it always interesting to see that there are common classics that every one among them knows: Wesley, Whitefield, Spurgeon and Moody. That is different from the mass culture now, in which everybody watches the same movies but has no classics.”

Regarding those communities, you speak about ecosystems. What do you mean by that?

“An ecosystem is a culture that is created through different knowledge institutions. In the medieval times, these were books, monasteries and the church. The revival movements included congregational journals, Bible colleges and study groups. In these ecosystems, education, edification and conversations took place.

Nowadays, digitalisation has transformed ecosystems. It gives room for creative opportunities. However, a challenge is that social media connections are very thin and unpersonal. This makes it harder to organise and undermines civil conversation. Further, if you follow the news online, you depend on anonymous algorithms. There is no board of editors you can speak with. It is also possible to target an individual user with propaganda – this is what happened in elections in the USA in 2016. It is not transparent at all. The discussions about the security of elections show that this is important for our society. I am not sure whether we can uphold our democratic culture on the screen.”

Could such ecosystems still function today?

“I think so. Some authors have spoken about the need for houses of reading, where people are trained to read together. Even digitally. People come together to read carefully and talk about that.”

In the past, we would have called that a school.

“Haha, yes. But today, schools need to do a much better job. They are focused on teaching how to handle new media. Still, they forget to teach the capacity to use the older formats, namely printed books. Pupils need to be trained in the reflective and transformative mode of reading. But that kind of reading is complicated on the screen.”

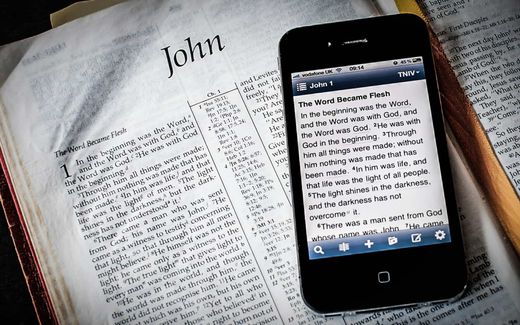

What is the difference between reading from paper and on the screen?

“The paper is physical. While reading a book, you can see how far you have come. You can browse back because you remember something at the top of an earlier page.

Most digital devices create an environment full of distractions, banners, hyperlinks and videos. That is not helpful for deep reading.

The internet is great for finding information but not for transformative reading. The deeper, prayerful and reflective reading is better done from a printed book or Bible than from a screen.”

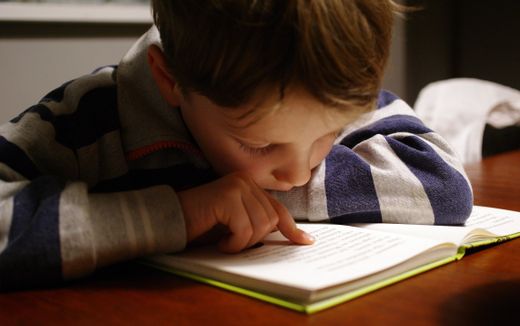

If we take the family as an ecosystem, parents read stories to young kids in many families. Could that help to pass on the art of reading to the next generation?

“Much research shows that reading to children enhances their vocabulary immensely. Children get access to a much richer language. In that sense, it is very educative.

It is also suitable for the parents. Some adults read professionally. But by reading for their children, they can return to reading for pure enjoyment. That can stimulate adults too to rediscover the joy of reading.”

For this interview, I have scanned many reviews, interviews and book fragments, all translated online from Swedish and Norwegian. Did I do something wrong?

“No, you didn’t. But, of course, you would have had a richer experience if you had read it in print and more slowly, from the beginning to the end. And yes, you would have come closer to the original in Swedish.

But I admit, for this book I have skimmed hundreds of articles and books. But some of them, I have read deeply and reflected upon. We need both techniques: informative and transformative reading. But since the latter is being threatened today, it is that one we must protect.”

In your book, you speak about your first Bible. Tell.

“As a kid, I read a lot. Comic books and phantasy. But when I was ten, I was called onto the stage in our Pentecostal church. We all stood in a line, and we had our names called. The children’s pastor of the church handed me my first own Bible.

Right when I received it in my hands, I realised this was a different kind of book. It commanded a different kind of respect than the usual storybooks I read. It was leather bound with a golden cross and leaf-thin paper. It was a very delicate book.

In our revivalist tradition, we are used to the combination of reverent reading and personal interaction with the text. So, I read it carefully, underlined some texts, and made notes in it. That was a means of dialoguing with the divine message in it. A Muslim would never do that in the Quran. But to me, it came naturally: the Bible was a holy book, read slowly for transformation – but also a book that invited me to dialogue. The medium is the message: The truth the Scripture conveys is not only in the printed words but also in how we read them.”

Related Articles