Review: Tyndale gave a model how to ‘plough’ through Bible translation

William Tyndale's statue in London. Shot from documentary

Christian Life

Even before William Tyndale translated the Bible into English, he had become “addicted” to the Word of God. And it was this addiction that drove him into his life’s work.

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

The 12-year-old boy was dropped at a college in Oxford. History tells that he used his time there tremendously well to study and became fluent in at least seven languages.

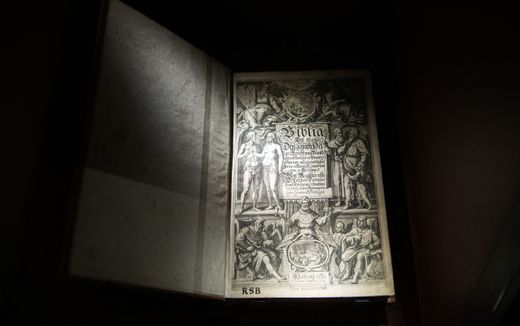

The documentary The Costly Legacy of Faithful Bible Translation shows Tyndale’s life in medieval England and Europe. This film is made by the Trinitarian Bible Society (TBS), the publisher of the Bible in which Tyndale’s work lives on till the present day.William Tyndale was born in (or shortly after) 1494 in a village north of Bristol. It was the time of the Renaissance and Humanism, and the professors said *ad fontes* and pointed to the sources. The young Tyndale followed this advice and became “addicted to the study of the Scriptures”.

He got to know Thomas Bilney, who wrote later about his reading in the Greek text of the New Testament, published in 1516 by Erasmus. In that, Bilney had found an answer to his experiences of guilt. “It is a true saying and worthy of all men to be embraced, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the chief and principal.” This was, Bilney said later, the “most sweet and comfortable sentence to my soul”. Tyndale might have had similar experiences, but they are perhaps not known.

The film shows the young and later older William Tyndale in drama, which is shown in sepia colours. The commentary and other present-day pictures are shown in normal colours, making it perfectly clear what is dramatised and what is not.

Afraid of the truth

The problem in Tyndale’s day was that the Biblical Scriptures had no priority at all in the church at that time. The church was “afraid of the truth,” the documentary says. The translation of the Bible was explicitly forbidden. Knowing God in a way that is not transmitted by the church was suspicious. Tyndale became a professor himself and started teaching. However, his doctrines were not valued by the Roman Catholic Church.

In a debate with other professors, Tyndale said he would do everything to ensure that “the ploughboy” would know more of God’s Word than the ordinary priest of the day. That was quite optimistic and also adventurous. But 500 years later, we see that it worked out.

Still, translating the Bible into English was easier said than done. In 1524, Tyndale had to evacuate to the European continent—even Luther’s Wittenberg in Germany—to do this. In 1525, the first parts of the New Testament were published in the city of Worms. Therefore, the English Bible celebrates its 500th anniversary this year. The documentary about Tyndale will go faster around the world than those New Testaments; thousands of copies had to be smuggled from Europe to England.

Tyndale did more than translate the Bible. He also wrote pamphlets against the Catholic Church. It seems that these pamphlets were the main reason for his persecution and final execution in 1536 in Vilvoorde (north of Brussels) because of heresy.

His work did not die, though. In 1604, the English King James demanded a new translation of the Bible that would integrate the best existing versions. Scholars have counted that 76 per cent of Tyndale’s Old Testament and 83 per cent of his New Testament still live on in the King James Version (KJV). Although there are countless newer Bible translations in English, the KJV remains their cornerstone. In other words, Tyndale’s work is still in use every day.

No doubt, Tyndale set a model for Bible translation work. His image that the “ploughboy” should know more about God’s Word than the average priest stimulates people to create newer versions and translations.

But no matter how clear the image of the simple farmworker may be, it still leads to debate among linguists. What did Tyndale really mean? Did Tyndale mean the Bible should be translated into the ploughboy’s language? Many people who defend a paraphrase Bible refer to Tyndale’s ploughboy.

Others approach this differently and say: Tyndale made a translation for the ploughboy. A Bible that could be accessed and understood by an unschooled land worker, to teach him about God and His Son. No doubt, the King James Version has served this purpose for many low-educated people throughout the centuries.

The documentary goes deep into Tyndale’s translation method, which is no surprise since the film was made by the Trinitarian Bible Society (TBS). This organisation uses two keystones regarding Bible translation work. The first is the use of the Received Text as the best original. The second is the method of formal equivalence since the words of the original are inspired.

For those reasons, Tyndale has authority. He “mirrored” the Hebrew and Greek syntax; the source languages were leading in his work, not the target language. It is not surprising that at the end of the documentary, the story leaves the historic account and moves on to another subject, namely the new visions on Bible translation that focus on the meaning rather than the words. The documentary tells us this “disconnects” the reader from the origin.

This is a fair debate that we may not ignore. There is still one question that is not often asked: Did Tyndale really think about this the same way we do? All the Bible translations during the Reformation were concordant; they followed the structure of the original language. That is their strength, and perhaps also their weakness.

Five hundred years later, we have many more options, from formal to functional equivalence. In Tyndale’s time, the only existing method was formal equivalence, which was considered proper and reliable. It worked not only for the Bible but also for simple messages.

Only in the twentieth century did the actual translation theory start to flourish. Today, students are presented with a broad palette of translation styles.

To say that Tyndale still must be leading in this assumes that Tyndale had the same options as we have and that he came to a well-thought-out conclusion. But this is not true. We have dilemmas that Tyndale never had. Tyndale may have chosen something else today, theoretically speaking.

Thankful

There is only reason to be thankful for Tyndale’s work. His translation of God’s Word has blessed many generations, and it still does. Because of that, it is proper to bring him back into the spotlight through this documentary and to learn from him.

Related Articles