Churches all over the world discuss Bible language

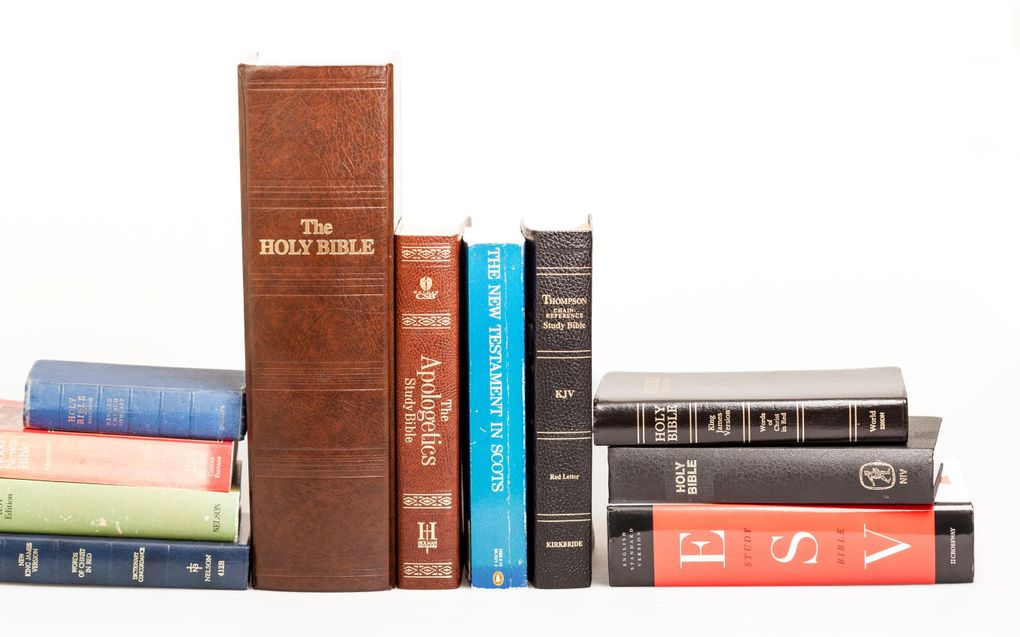

Several English Bible versions. Photo RD, André Dorst

Christian Life

God wants to speak to people, and He has given the Bible for that purpose. But in some places, this old book has difficult language. How clearly can He talk to us?

Stay up to date with Christian news in Europe? Sign up for CNE's newsletter.

The evening services were devoted to a series on David. The minister, now the late John J. Murray, read 1 Samuel 19 from the King James Version. In verse 7, “And Jonathan called David”, a mischievous boy moved his hand to his ear as if he were holding a telephone. I reckon it very likely that I burst out laughing in that church in the centre of Edinburgh.

The sentence “And Jonathan called David” is a funny example of how language changes over time. When this was written in the days of the Old Testament, the telephone was still not invented, and neither was that when the King James Version (KJV) was published in 1611.

Because of new inventions and other reasons, the meaning of words changes. There are even examples of expressions that received a meaning opposite the original. That has consequences for churches that are used to having old Bible versions.

I come to this because in my country, the Netherlands, the discussion about a textual update of the Statenvertaling flared up again recently. The Statenvertaling is the Dutch King James, the Bible translation from the early 17th century. Many churches cherish this as part of the Reformation heritage and try to use this version still today. Through the ages, there have been numerous updates. But usually, updates are preceded by lengthy discussions about their necessity and motives.

Still, the old text is difficult. Every new generation has to get used to both the complex structure of the original languages and the outdated words from their own language. In other words, what is inspired and unchangeable, and what could be updated? It is not always easy to differentiate between old Hebrew and 17th-century Dutch.

Sometimes, people complain about this “typical Dutch problem” and that we must get wiser. But that is not the case. This is a worldwide phenomenon. All churches (especially the more traditional ones) recognise this. The example of David and Jonathan makes this clear for the English-speaking world.

Back to Mr John J. Murray: In a personal conversation, this Scottish minister once said: “For me, the King James is the translation that was given during the church’s heyday.” He did say he saw room for the New King James Version (NKJV, a revision from 1982) but not for a new translation. By the way, this was before the English Standard Version (ESV) was introduced.

Saying that a Bible version is a gift from the church’s heyday is a typical historical argument. Coming from a Dutch Calvinist tradition, I can completely understand that. But I also realise that such an argument does not carry authority in every country. In Scotland, Mr Murray could say that his Presbyterian church was closely linked to national history and that the church wants to continue that tradition.

However, many countries do not have a Reformed tradition, so there is nothing to continue. I noticed this when I came to South Africa as a student in the 1990s. There, they had just said goodbye to the Totius Bible (a 1933 version in the style of the Statenvertaling and the King James) and switched to the Nuwe Vertaling from 1983.

The ease with which most churches made this switch would have been impossible in the Netherlands. This is logical because South Africa is an immigration country with a very different experience of history and tradition. I think it is easier for them to say farewell to something from old times than we, as Europeans, would do.

For me personally, that new Afrikaans version became one of the sources I used to learn Afrikaans. That Bible is an excellent piece of work. But I also understood the critical voices that asked: Is this everyday language entirely faithful to the original text?

I also remember visiting Protestant Christians in another immigration country: Israel. Of course, this is the country of the Biblical tradition. But it is not a country with an ecclesiastical tradition within which a particular Bible translation is passed on. In conversations with Jewish Christians, I did not notice that they felt any particular loyalty to the past. Of course, this gives an inner liberty to make choices that would not have been self-evident to the Dutch or the Scots.

In my own country, I sometimes notice that people hope that this discussion will pass, that nothing changes, and that we all go on at length with the same Bible version. But when I look at the world around me, I give them little hope.

Churches all over the world have the same question: How can we pass the Word of God in plain language? And since the whole global church is in this same boat, we are wiser if we listen to each other. And let’s remember that the Bible is not just an ancient text. It is God’s Word that He has given with a purpose: to speak to people.

Related Articles