Ukrainian seminaries learn lessons in wartime resilience

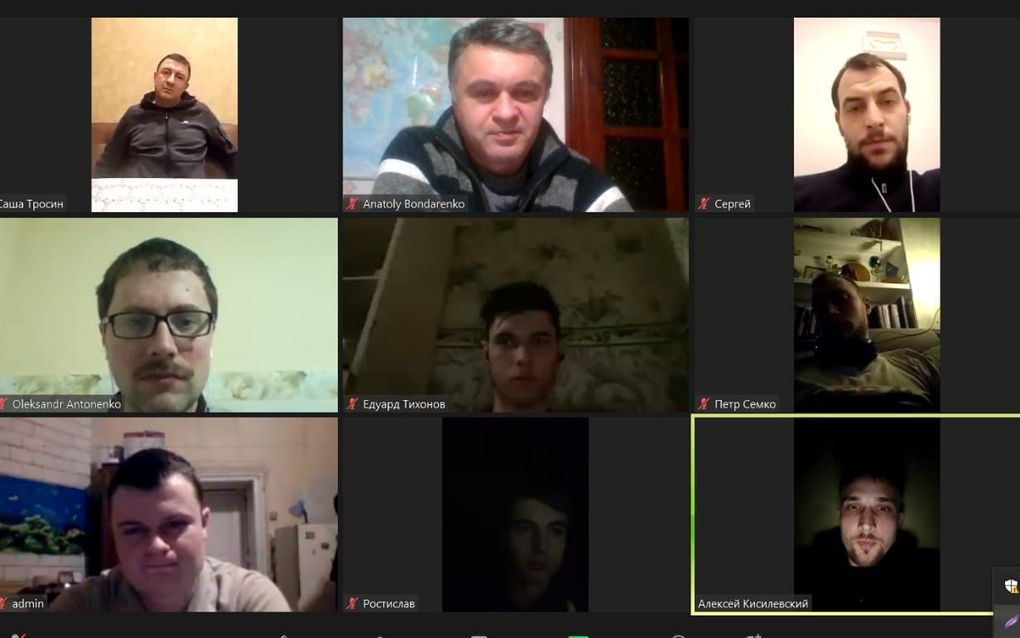

Online lessons at the Odesa Theological Seminary. Photo OTS

Eastern Europe

As six missiles rained down near the campus of the Ukrainian Adventist Theological Institute (UATI), Viacheslav Korchuk kept praying. Despite one land mine being metres close to destroying the professor’s home, he and his wife continued to stay and teach.

With the war still raging, many theological seminaries have found themselves adjusting their schedules and programs to accommodate an uncertain future.

As in the case of Korchuk’s Ukrainian Adventist Theological Institute UATI, in Bucha, 30 kilometres from Kyiv, their 82-student body will be working online until 2023. Holding on-campus classes is still not possible, as many have moved outside of the city. Before the war, professors from Russia would teach at their seminaries. Now, that is no longer possible. Although challenges remain, some representatives from Poland and Romania have stepped in to help students continue their studies, which has been a blessing, according to prof. Korchuk.

Mission in own country

At the beginning of the war, Bucha made headlines across the world, as it had become an epicentre of widespread damage and death from Russian artillery. Despite efforts to rebuild the area, the instructor of soteriological studies said that it will take time to resume all on-campus functions, especially its mission work.

Now, during the war, the seminary sees a mission in their own country. Its ministry team hopes to send a truck full of supplies to war-torn Kharkiv. Since Ukrainians recently liberated the north-eastern city, the journey may be safer, he says.

As for now, he does see an end to the war and a purpose for staying in his country. While most men under 60 years old cannot leave because of the war, Korchuk has been given clearance not to fight, which has allowed him to serve God in a greater capacity.

“As pastors, we should stay where the people are and help them,” he says. “We have the Hope in Jesus and believe that He will come very soon. When He will come, all wars will be ended in the world”.

Ministry in community

Oleksandr Geychenko is another professor who decided to stay in Ukraine. The Odesa-based Odesa Theological Seminary, a city that borders the Black Sea, soon found itself becoming a ministry in the community. Seminary students and the area’s Baptist Association provided food and shelter for war-weary refugees en-route to other countries. Some who travelled by car saw their gas tanks refuelled and their maintenance fees covered by the staff.

“We were not ready for that, but we were trying to help,” he says regarding the situation.

International agencies later took over, which allowed the seminary to focus on resuming classes for its now 100 students. Approximately 300 students previously attended, but the events surrounding the war have led to a decline in enrolment. For those that are attending and living near the area, classes have continued on its campus.

Geychenko says that groups are kept small, and shelters have been designated on campus in case of air raids. However, most are over the age of 20 and cannot attend stationary classes because of family or work. As solution, the seminary offers distance learning options and sends instructors to teach courses in other Ukrainian cities. He says that in the future, they hope to add more full-time distance learning courses, so students can continue at their current location. As for now, a hybrid mode that includes some online and on-site classes is the tentative plan for the current academic year.

Looking ahead, Geychenko does not see an end to the war – at least not yet.

“The mentality of Russian officials is no turning back. Unless we have full-fledged support, the Ukrainian army cannot do it,” he says.

Stress levels

As the war continues to change the psyches of young ministers, more programs will be needed. Geychenko says that he hopes to create more courses that will address the growing needs of his students. Because of the high-stress levels, pastors have to be trained in care for disorders like PTSD. He also wants to incorporate programs in pre-med training and first aid, as he feels that leaders should care for both the mind and the body.

“The church needs to be equipped to do this job properly,” he says regarding the area of ministering to others.

Shelter for refugees

Evangelical Reformed International Seminary ERSU based in Kyiv, is another seminary that had to reinvent itself after the war began. Practical theology lecturer, Oleksiy Blyzniuk, says that they have found themselves as a hub during the war, where they have acted as a temporary shelter for Ukrainian refugees. Almost 100 per cent of their student body is currently men, and Blyzniuk says that they have had to contend with the nation’s requirement of having them stay and fight in the country. For those fighting on the front lines, the seminary has worked with a local Baptist church to make armour.

When the war broke out, Blyzniuk and his wife fled to Lviv for two months. When they returned that May, the city appeared empty.

“It was quite a picture. Psychologically, it was very hard,” he said.

Now, as they continue to build a future for their students, uncertainties remain for their 41 students currently studying there. Although they have had six new enrollees this year, many of their existing ones are still scattered throughout the country. Online classes have been set up as a temporary solution – for now.

“When they come to campus, they leave their families. They need to be at home,” he says.

Blyzniuk also said that while no direct hits have been reported on their campus, the situation remains risky. Air raid sirens have become an everyday occurrence.

“Everything can be changed if one missile hits this city,” he said.

All classes on Zoom

Merle Messer, an American who has travelled as a professor for Reformed International Theological Seminary RITE-Ukraine in Donetsk and Kyiv, says that it had to suspend their classes for several months when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. Shortly after, they had to move their seminary to Kyiv. Now, the seminary has had to adapt to another move by offering Zoom classes to its 18 students, as many are scattered throughout Ukraine. According to Messer, Zoom offers a less personalised experience than on-site classes.

“You don’t get the interaction that you do in person…As soon as we can get back there, we’ll get back there,” he says.

Prayer is focus

As for Ukraine’s main denomination, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the war has not stopped young people from seeking a vocation in church leadership.

Nadia Kuzma, who works as an English teacher and translator at Pochaiv Spiritual Seminary in Ternopil (a city near Lviv), says that they have seen 50 new students enrol for their BA program in theology, which is still being taught on campus. At least 30 additional students are currently studying by correspondence, where they prepare individually and come for the campus exams in Catechism, Old and New Testament studies, apologetics, as well as tests in English, Greek, and Romanian.

As they continue on-site instruction for most students, prayer remains the focus for an unknown future.

“Every day in Orthodox churches, people pray for peace,” she says.

Related Articles